A Tapestry of Hidden Love

In the sultry heat of a West African night, where the air hums with the rhythm of cicadas and the scent of jasmine lingers, queer love has always burned bright—yet, for centuries, it’s been cloaked in shadow. The Guardian’s poignant words, “Queer people were living, loving, suffering, surviving – but invisible,” cut to the heart of a history that pulses with defiance, desire, and resilience. West Africa’s queer stories, though often erased by colonial pens and modern prejudices, are as vibrant as the kente cloth that drapes the shoulders of its people. This is a tale of bodies entwined under moonlit baobab trees, of whispered promises in bustling markets, and of hearts that dared to love against the grain of silence. Let’s unravel this tapestry, thread by sensual thread, and reclaim the queer history of West Africa with unapologetic fervor. It’s time to make the invisible seen.

Precolonial Passion: A Queer Eden Before the Storm

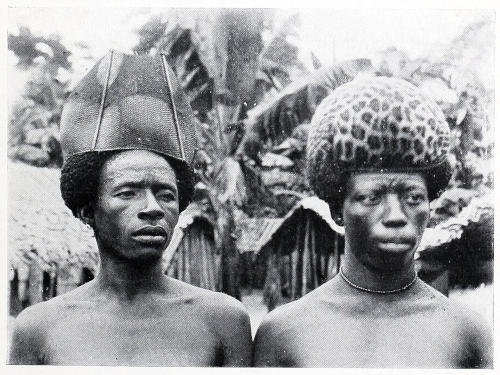

Before the ships of empire docked on West African shores, before the Bible and the penal codes rewrote desire, queerness flourished in ways that defy modern labels. In the Yoruba lands of what is now Nigeria, the word adofuro—a term for someone who loves through anal intimacy—existed as naturally as the yam harvest. This wasn’t a slur but a descriptor, as old as the culture itself, woven into the oral traditions of a people who saw love as fluid as the Niger River. Queerness wasn’t an aberration; it was a thread in the communal fabric. Among the Hausa in northern Nigeria, yan daudu—effeminate men who often took male lovers—were recognized as spiritual and social figures, sometimes revered, sometimes playful, always integral. “In my local language (Yoruba), the word for ‘homosexual’ is adofuro... it is as old as the Yoruba culture itself,” writes Nigerian gay rights activist Bisi Alimi, reminding us that queerness is no Western import.

(In precolonial Angola, the Chibados or Quimbandas, male diviners who lived as women, were celebrated for their spiritual potency. Dressed in flowing garments, they married men, their unions seen as sacred, their presence a bridge to the divine. The Igbo and Yoruba didn’t assign gender at birth, waiting instead for a child’s energy to reveal their place in the world. The Dagaaba of Ghana assigned gender based on spirit, not anatomy, a practice that danced with the fluidity of the cosmos. Imagine a world where love wasn’t boxed into binaries, where a man could love a man, a woman could marry a woman, and gender was a spectrum painted in starlight. These weren’t anomalies but expressions of a culture that celebrated diversity as a gift from the ancestors.

(Picture a moonlit festival in the Agikuyu lands of Kenya, where women married women in sacred unions, their love as legitimate as any other. These woman-woman marriages, documented in a 2000 study by Wairimũ Ngarũiya Njambi and William E. O’Brien, were not hidden but celebrated, a testament to the fluidity of gender and desire. In Senegal, once whispered as the “gay capital of West Africa,” trans women and queer men moved freely, their lives woven into the vibrant tapestry of Wolof culture. Their love was no secret; it was a song sung in the open, until the colonizers arrived with their hymnals and their chains.

The Colonial Shadow: Erasing the Queer Spirit

Then came the storm. European colonizers, with their rigid moral codes and Christian dogma, cast a shadow over West Africa’s queer Eden. The British, French, and Portuguese imposed laws that criminalized same-sex love, branding it “unnatural” and “sinful.” In Ghana, the Penal Code of the 1860s—still a relic today—punished “unlawful carnal knowledge,” a vague term that became a whip against queer bodies. The irony is bitter: the same colonizers who called African sexuality “primitive” introduced the homophobia now falsely claimed as “African tradition.” As Bisi Alimi notes, “The idea that homosexuality is ‘western’ is based on another western import – Christianity.”

(In the Buganda Kingdom of Uganda, King Mwanga II, openly gay and unapologetic, faced no scorn from his people until white missionaries brought their condemnation. His love for men was as natural as the Nile’s flow, but the Christian church branded it an abomination. Across the continent, colonial powers excised queer stories from the record, replacing them with a narrative of shame. Ethnographers like Sir Richard Burton, who once mapped Africa’s sexual diversity, later erased it, claiming queerness was absent south of the Sahara. Yet the evidence was there: Bushman artwork depicting same-sex intimacy, oral traditions of same-sex rites of passage, and the very languages that named love in all its forms.

(The violence of this erasure wasn’t just cultural; it was physical. Queer Africans were forced into hiding, their love relegated to whispers in the dark. The Chibados were demonized, their sacred roles stripped away. The yan daudu were marginalized, their vibrant presence pushed to the fringes. By the time independence swept across West Africa in the 20th century, the colonial legacy of homophobia had taken root, fertilized by missionary zeal and Western religious fervor. The queer spirit, once celebrated, was now a fugitive in its own homeland.

Reclaiming the Narrative: The Literary Revolution

Fast forward to 2005, and a spark ignites in Nigeria. Jude Dibia’s Walking With Shadows, the first West African novel to center a gay protagonist, bursts onto the scene like a Molotov cocktail of truth. The story of Ebele “Adrian” Njoku, a man grappling with his sexuality in a society that demands his silence, is a radical act of visibility. “Literature has the power to name what society refuses to see,” Dibia declares, and his novel does just that, peeling back the layers of erasure to reveal a beating, queer heart. The backlash was fierce—publishers balked, friends turned away, and Dibia was blacklisted from literary spaces—but the book’s impact was undeniable. As Ainehi Edoro, founder of Brittle Paper, notes, “For a long time, queer characters in African literature were either invisible or treated as symbols of crisis... Dibia wrote a novel that centred a gay Nigerian man as a full human being.”

(Dibia’s courage opened the floodgates. Chinelo Okparanta’s Under the Udala Trees (2015) wove a lesbian love story against the backdrop of the Nigerian Civil War, its pages dripping with the ache of forbidden desire. Imagine two women, their hands brushing under the shade of a udala tree, their love a quiet rebellion against a world tearing itself apart. Romeo Oriogun’s Burnt Men (2016), the first queer poetry collection from Nigeria, sang of bodies scorched by society’s gaze yet unyielding in their passion. Chike Frankie Edozien’s Lives of Great Men (2017) and Unoma Azuah’s Embracing My Shadows (2020) carved out space for gay and lesbian memoirs, each a testament to survival. “Each time I do something that examines the fullness of our lives, I know that I’m continuing the work Jude began,” Edozien says, his words a torch passed from one storyteller to the next.

(These works aren’t just literature; they’re acts of defiance, love letters to a community rendered invisible. They channel the spirit of queer nightlife—think of Lagos’s underground clubs, where bodies sway to Afrobeats, sweat and desire mingling in the air. Picture a drag queen in a sequined gown, lips painted crimson, commanding the room with a wink and a twirl, her performance a middle finger to the Same Sex Marriage Prohibition Act of 2014. These stories are the pulse of a new West African queer renaissance, where writers, poets, and activists are rewriting the narrative with ink as bold as their hearts.

The Erotic as Resistance

Let’s get wild for a moment. Queer love in West Africa isn’t just about survival; it’s about pleasure, the kind that sets your skin ablaze. In the face of laws that criminalize desire, every kiss, every touch, every stolen glance is an act of rebellion. Imagine two men in a Accra alley, their lips meeting in the shadow of a streetlamp, the world fading to nothing but the heat of their breath. Or a trans woman in Dakar, her hips swaying to mbalax rhythms, her body a canvas of self-love in a world that demands her shame. The erotic is political, a refusal to let joy be legislated away.

In Unoma Azuah and Claire Ba’s anthology Wedged Between Man and God, queer West African women tell stories of “sexistential crises,” a term coined by contributor Kemi Lade to describe the turmoil of discovering her bisexuality in a world that demands she choose. These women don’t just survive; they thrive, their bodies temples of defiance, their love a middle finger to patriarchy. One story tells of Habiba, forced into an arranged marriage to a man, her heart still tethered to a woman she can never claim. Yet even in her cage, she finds ways to resist, carving out moments of pleasure in secret. “Appearance rather than truth is held supreme,” writes Tanamia Ilunga, but these women refuse to let their truth be buried.

(Pop culture amplifies this rebellion. Beyoncé’s Lemonade, with its nods to Yoruba spirituality and fluid expressions of love, resonates with West Africa’s queer youth, who see their own defiance in her unapologetic blackness. In Nigeria, queer filmmakers like Uyaiedu Ikpe-Etim, director of Ifẹ, craft stories of lesbian love that pulse with sensuality and courage. Their films are like a night at a queer ball, where every step is a declaration: We are here, we are fabulous, and we will not be silenced.

The Fight for Visibility: Activists and Archives

The literary revolution is only part of the story. Across West Africa, activists are fighting to reclaim queer visibility, often at great personal cost. Bisi Alimi, who came out on Nigerian television in 2004, faced death threats and exile but continues to challenge the myth that queerness is “un-African.” “Prior to reading , I had never really read any book as personal and relatable as that,” he says, crediting Dibia’s novel with giving him the courage to live his truth.

(In South Africa, the GALA Queer Archive, led by figures like Keval Harie, preserves the stories of queer Africans, from precolonial ancestors to modern activists. “There isn’t this universal and monolithic queer-lived experience in Africa,” says Boniswa, a 28-year-old queer South African, her words a reminder that queerness is as diverse as the continent itself. In Kenya, trans activist Arya Jeipea Karijo fights for narrative change, challenging colonial legacies that branded queerness as foreign. These activists are the griots of today, their voices a chorus against erasure.

(Yet the fight is far from easy. In Nigeria, the 2014 Same Sex Marriage Prohibition Act forced many, like Dibia, into exile. In Ghana, recent anti-LGBTQ+ bills have sparked violence and fear. But even in the face of this, queer West Africans dance, love, and create, their resilience a testament to the human spirit. As Chike Frankie Edozien writes, “We’ve been diverse as long as we’ve existed.”

(A Future Forged in Love

So where do we go from here? The queer history of West Africa is a phoenix, rising from the ashes of colonial erasure. It’s in the poetry of Romeo Oriogun, the activism of Bisi Alimi, the films of Uyaiedu Ikpe-Etim, and the secret kisses stolen under starlit skies. It’s in the drag queens of Lagos, the trans women of Dakar, and the nonbinary storytellers who refuse to be silenced. This is a history that doesn’t just survive; it thrives, wild and unapologetic, like a Fela Kuti riff cutting through the night.

Imagine a future where West Africa’s queer children walk hand in hand, their love no longer a fugitive. Picture festivals where yan daudu dance openly, where Chibados are once again revered, where love is as free as the harmattan wind. This future isn’t a dream; it’s a promise, one that queer West Africans are forging with every story, every protest, every act of radical love.

As we close this chapter, let’s channel the campy glamour of a queer ball, the sweat and glitter of bodies moving in defiance. West Africa’s queer history is no longer invisible—it’s a supernova, blazing across the sky, demanding to be seen. Let’s honor it by living loudly, loving fiercely, and never letting the world forget: we were always here, and we always will be.

0 Comments