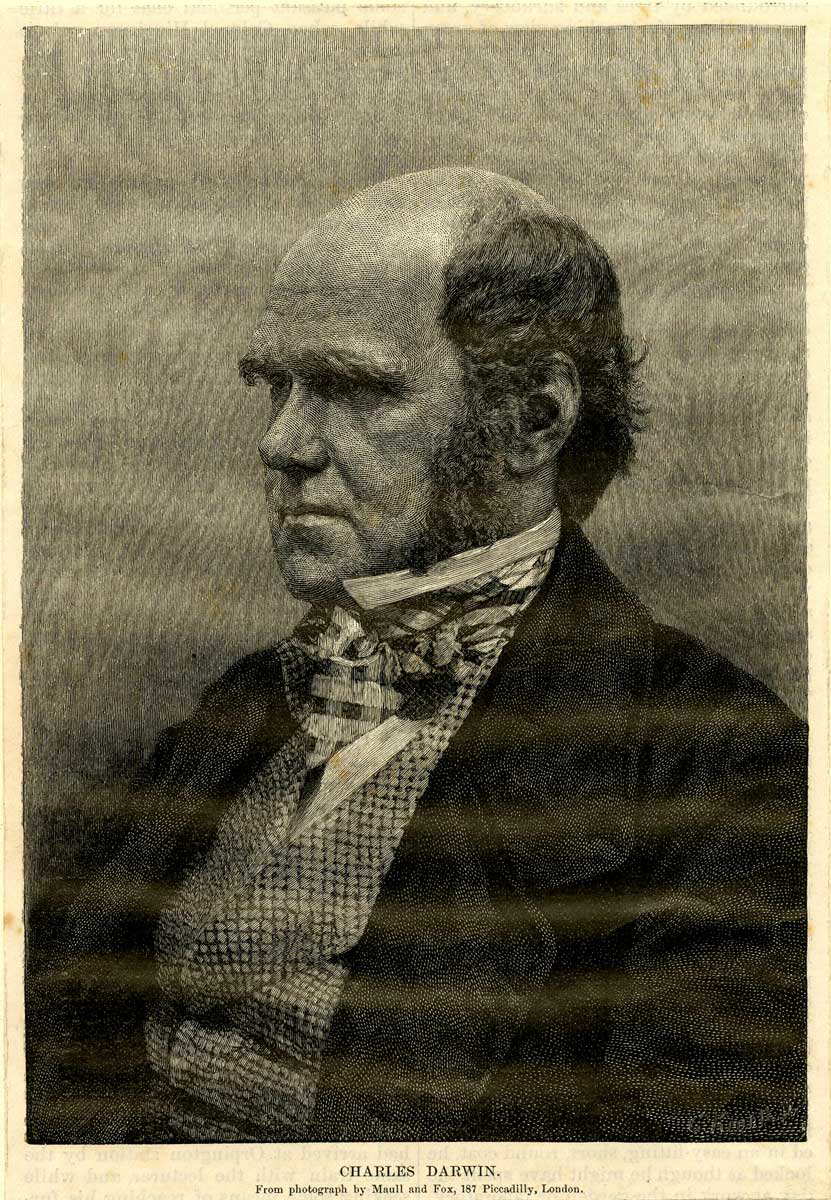

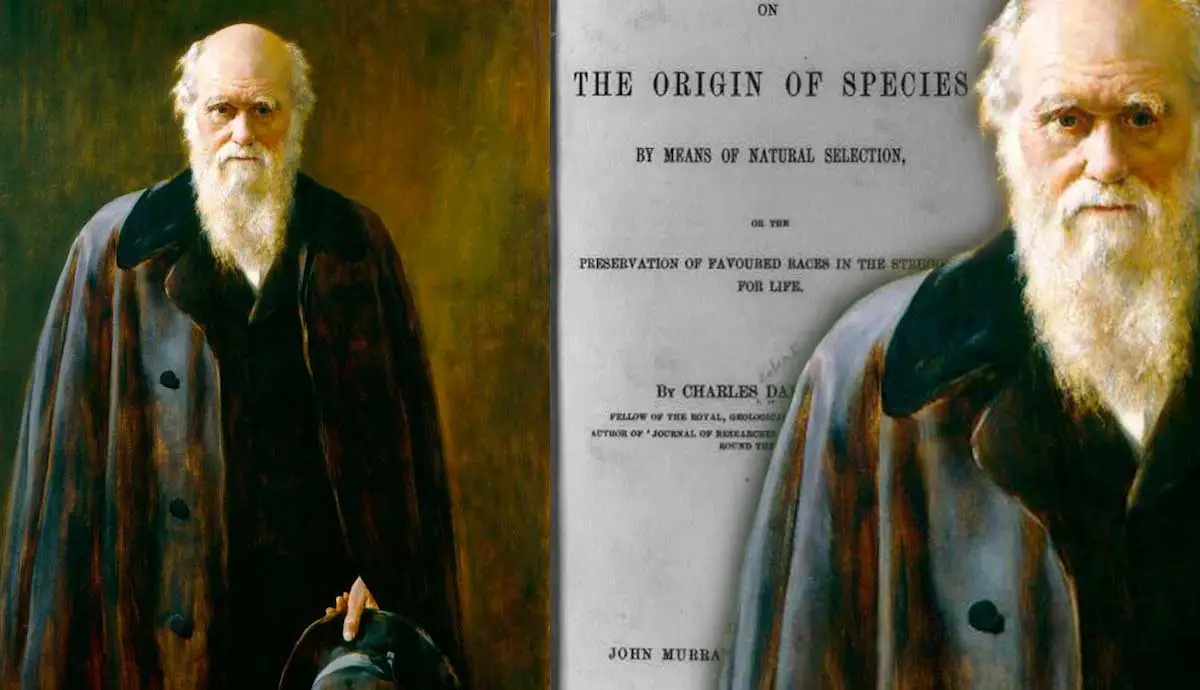

Charles Darwin was fully cognizant of the inevitable scrutiny he and his family would face due to the publication of On the Origin of Species. So, what motivated him to undertake such a controversial endeavor?

In his youth, Charles Darwin inhabited a world where the prevailing belief held that life on Earth was static and unchanging since its inception. The entrenched notion of Special Creation, especially prevalent in the early nineteenth century, dictated a clear demarcation between humanity and the rest of the natural world. Darwin's groundbreaking theory, as articulated in On the Origin of Species and subsequent works, directly challenged these entrenched beliefs, leading to a significant backlash.

Before Darwin's seminal work, the prevailing scientific consensus rejected the idea of evolution. Despite a lineage of intellectual inquiry stretching back to Aristotle and including his own grandfather, Erasmus, Darwin initially adhered to the conventional theological principles of his time. The concept of evolution posed numerous challenges, particularly the requirement of vast expanses of time—a notion at odds with prevailing scientific thought, which considered the Earth to be relatively young.

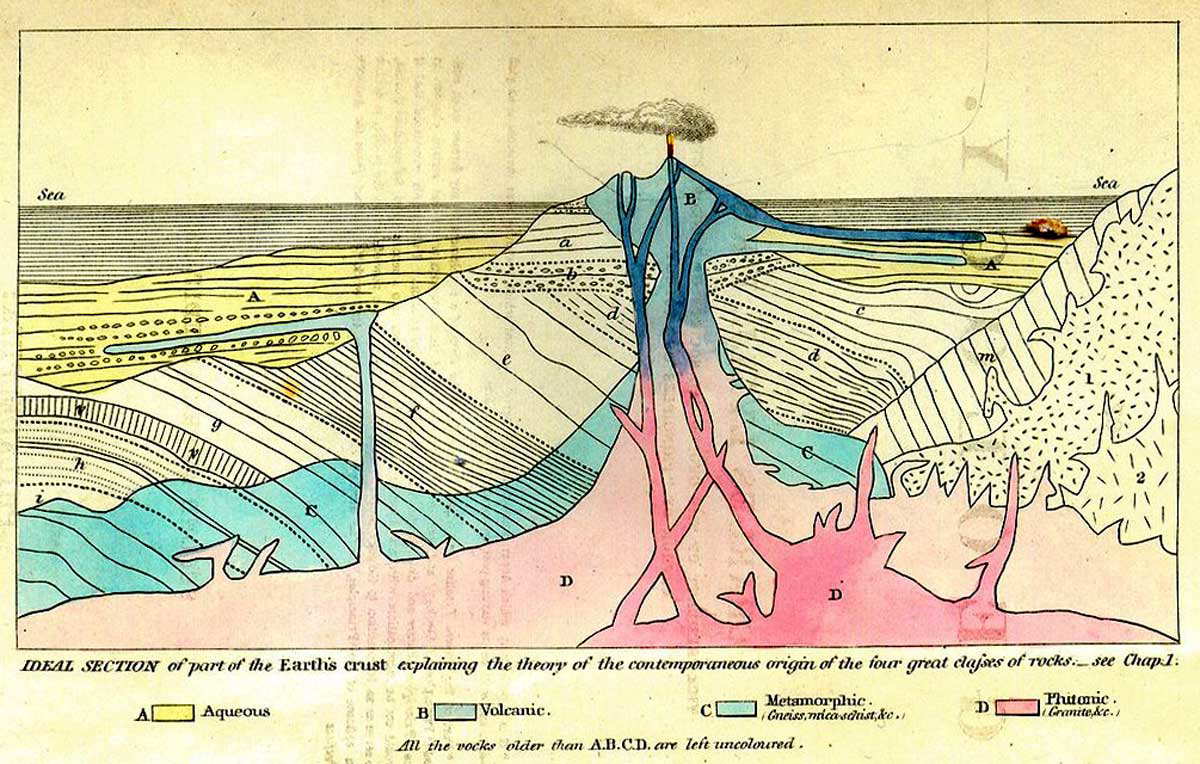

The prevailing belief, popularized by Bishop Ussher in the seventeenth century, placed the age of the Earth at slightly under six thousand years. Although some allowed for a slightly longer timespan, dissenting voices emerged, particularly from the field of geology, which progressively amassed evidence suggesting an immensely greater age for the Earth and its geological formations.

Cras eget sem nec dui volutpat ultrices.

Cras eget sem nec dui volutpat ultrices.

It was evident that artificial selection, practiced among domesticated species, was both feasible and actively employed. In the seventeenth century, Roger Bacon observed that farmers routinely selected or bred subsequent generations of crops or livestock based on desired traits. For instance, if farmers sought heavier pigs or larger corn cobs, they deliberately bred the fattest pigs or planted corn kernels from stalks bearing larger cobs. Similarly, the proliferation of different dog breeds showcased the effects of this selective breeding process.

The definition of species as entities capable of producing similar offspring led Carl Linnaeus to embark on systematic categorization in the early eighteenth century. The concept of "like begets like" required clarification due to widespread belief in spontaneous generation from the earth. Additionally, there was a common notion that disparate animals could mate, potentially yielding deformed offspring or chimeras.

Erasmus Darwin, a prominent figure of the Enlightenment, proposed the idea of animal evolution. His notions were echoed and expanded upon by Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, who suggested that animals acquired traits during their lifetimes in response to environmental pressures, outcompeted others within their species, and passed on these acquired traits to their offspring. While Lamarck's notion of giraffes stretching their necks to reach higher leaves and passing on this trait to their offspring was ultimately proven incorrect, the concept of evolution driven by environmental conditions and competition gained traction among scholars.

Darwin, influenced by Thomas Malthus' theories on overpopulation, which he encountered soon after his voyage, also embraced the idea. Malthus proposed that most plants and animals produced offspring in excess, but environmental factors such as food scarcity, conflict, disease, and predation regulated population growth.

Darwin’s Education

Cras eget sem nec dui volutpat ultrices.

Cras eget sem nec dui volutpat ultrices.

At his father's insistence, Charles enrolled in medical school at Edinburgh, where he encountered various theories on Earth's formation. One notable theory, proposed by the self-taught geologist Hutton, known as Uniformitarianism, suggested that incremental processes over vast spans of time shaped the Earth's features, including its mountains.

Despite the intellectual stimulation in Edinburgh, Darwin's medical studies came to an abrupt halt when he found himself unable to endure witnessing surgeries performed on unanesthetized patients, particularly a child. This experience led him to abandon his medical pursuits.

Subsequently, Darwin pursued studies at Cambridge with the intention of becoming a clergyman. Influenced by prominent geologist Adam Sedgwick and inspired by a lecture from renowned botanist Reverend George Henslow, Darwin developed a keen interest in natural history, particularly beetle collection. Under Henslow's guidance, he honed his skills in observation and inference, which proved invaluable later.

Despite struggling with theological studies, Darwin managed to graduate from Cambridge, surprisingly achieving a respectable tenth place in his class through intense last-minute studying. Initially aiming for a clergy position, Darwin's trajectory shifted when he was recommended by Henslow for the naturalist role aboard the HMS Beagle, altering the course of his career.

The Voyage That Changed Darwin’s Life

Cras eget sem nec dui volutpat ultrices.

Cras eget sem nec dui volutpat ultrices.

Following discussions with his father and a favorable meeting with Captain FitzRoy, Darwin secured the position of naturalist aboard the HMS Beagle. FitzRoy's primary task was to conduct surveys of the waters surrounding South America and the Pacific. Initially slated for a three-year duration, the voyage extended to five years, spanning from 1831 to 1836, during which Darwin spent a significant portion of his time on land rather than at sea.

Darwin meticulously documented his observations during the voyage, exhibiting a breadth of knowledge across various scientific disciplines. Upon his return, he authored a widely-read book recounting the journey, which remains in publication today. This work not only chronicled his own experiments and findings but also referenced the contributions of others, resulting in a comprehensive exploration of South America's flora, fauna, and geology presented in an engaging narrative style.

While aboard the Beagle, Darwin immersed himself in Lyell's Principles of Geology, which advocated for Uniformitarianism and emphasized long geological timescales. Finding ample evidence to support Lyell's theories, Darwin corresponded with England, sharing his observations. Despite his endorsement of Lyell's geological theories, Lyell remained skeptical of Darwin's evolutionary ideas, particularly regarding human evolution.

Darwin's collection efforts yielded numerous specimens previously unknown in Europe, including the famous finches, which, contrary to their name, were actually a type of tanager. Upon his return, Darwin collaborated with ornithologist John Gould to classify these specimens, noting the variations in beak morphology among different island populations. This observation fueled Darwin's realization that geographical isolation could drive species diversification, ultimately leading to the emergence of distinct species.

Back to England

Cras eget sem nec dui volutpat ultrices.

Cras eget sem nec dui volutpat ultrices.

Upon his return to England in 1836, it became evident that Darwin had diverged from the path toward a clerical career, as his absence had sparked widespread interest among the scientific community. Surprisingly, it was not his contributions to biology that initially garnered him fame, but rather his insights in geology.

Presenting a trove of remarkable fossils, Darwin captivated the Geological Society with evidence of marine life long extinct, discovered at elevations of 14,000 feet in the South American mountains. Additionally, he recounted witnessing land elevation of eight feet following an earthquake—a phenomenon aligning with Lyell's theories on gradual geological processes over immense time scales.

Moreover, Darwin's innovative hypothesis regarding coral reefs offered a fresh perspective to his peers. He proposed that as islands subsided, new coral reefs formed atop dying ones, indicating not only land elevation but also subsidence in various regions—an idea that challenged conventional geological understanding.

Building a Base to Present His Theory

Cras eget sem nec dui volutpat ultrices.

Cras eget sem nec dui volutpat ultrices.

By 1837, evidence from his diaries suggests that Darwin had commenced formulating his theories on evolution; however, the prevailing social and political turbulence posed a significant obstacle. England in the 1830s and 1840s was marked by societal unrest, with the working class clamoring for increased civil rights. During the early years of their marriage, the Darwins resided in London, where much of the violent protests unfolded. Despite Darwin's alignment with the Whig party and his empathy for the protesters' cause, the tumultuous environment was unsuitable for raising a family or introducing a contentious theory susceptible to immediate politicization. Consequently, the couple, along with their young children, opted to purchase a residence in the countryside—Down House—where Darwin spent the remainder of his life and penned his most renowned works.

Darwin was acutely aware of the potential backlash rooted in religious dogma, which he anticipated would be formidable, even within his personal life. His marriage to his cousin, Emma Wedgwood, provided him with a confidante with whom he could discuss his ideas on natural selection prior to proposing. While Emma harbored deep affection for Darwin, she remained profoundly troubled about the state of his soul throughout their life together, fearing that his beliefs might hinder their eternal companionship after death. Although Darwin didn't share her apprehensions, her concerns weighed heavily on him. Moreover, with a growing family—seven out of ten children survived to adulthood—and a respected stature within the scientific community, Darwin had compelling reasons to delay the publication of his theories.

Cras eget sem nec dui volutpat ultrices.

Cras eget sem nec dui volutpat ultrices.

However, as Darwin delved deeper into his research, his confidence in the validity of his theory of natural selection grew stronger. Additionally, he recognized the need to bolster his reputation as a biologist, as he was predominantly perceived as a geologist among his peers. He was wary of risking dismissal of his ideas due to perceived overreach beyond his field of expertise. Consequently, Darwin embarked on an extensive study of barnacles, a prolonged endeavor aimed at enhancing his credentials and refining his understanding of natural selection. His examination revealed a spectrum of barnacle forms, including hermaphroditic, heterosexual, and various intermediate configurations where males were attached to females, amusingly termed "little husbands" by Darwin. Through eight years of meticulous study and classification, Darwin established that variation was not an anomaly but a fundamental aspect of nature.

By the 1850s, societal dynamics were undergoing significant shifts. The industrial revolution, which propelled England into the latter half of the century, brought forth not only economic prosperity and employment opportunities but also fostered a receptiveness to new ideas among the populace. Encouraged by his friends, particularly Lyell, who expressed concerns about potential preemption, Darwin faced mounting pressure to publish his findings.

The Final Push: Alfred Russel Wallace

Cras eget sem nec dui volutpat ultrices.

Cras eget sem nec dui volutpat ultrices.

By 1854, amidst a shifting intellectual climate and having firmly established himself as both a geologist and a biologist with numerous publications in both domains, Darwin embarked on the organization of his notes. In 1856, he commenced work on a substantial tome outlining his overarching theory. Despite lacking a sense of urgency, Darwin's tranquility was abruptly disrupted on June 18th, 1858, by a startling letter from Alfred Russel Wallace.

Prior correspondences between Darwin and Wallace had touched upon the topic of evolution, with Darwin even purchasing specimens from Wallace, a dedicated specimen collector who financed his global expeditions through the sale of his findings to affluent collectors to support his passion for biological science.

Wallace's manuscript bore striking resemblances to Darwin's own work, to the extent that some passages from Darwin's book reappeared with minor alterations in Wallace's paper. Initially inclined to cede all credit to Wallace, Darwin's colleagues dissuaded him from doing so. Instead, a joint presentation featuring Wallace's paper, Darwin's 1844 outline, and a letter from 1857 outlining Darwin's theory to another colleague, was delivered at the Linnean Society on July 1, 1858. Neither Wallace nor Darwin was in attendance; Wallace was still conducting research in the Malay Archipelago, while Darwin was grieving the loss of his tenth child, who succumbed to scarlet fever on June 28th at the age of eighteen months.

On the Origin of Species: The Theory of Natural Evolution

Cras eget sem nec dui volutpat ultrices.

Cras eget sem nec dui volutpat ultrices.

In its simplest form, natural evolution hinges on two key principles: variation and speciation. Variation refers to the fact that offspring are not exact replicas of their parents; rather, slight differences exist between them. Selection, on the other hand, involves the environment favoring life forms that are better suited to their surroundings.

Surviving individuals, possessing variations that confer advantages over others in their species, proceed to reproduce. Their offspring inherit more of the traits that enabled their parents' survival, albeit with further variations. As competition intensifies with a burgeoning population, natural selection becomes increasingly rigorous.

Darwin's contribution didn't lie in proving the occurrence of evolution in general among species; this concept had long been established in agricultural practices. Rather, Darwin elucidated the mechanisms driving evolution in the natural world. He demonstrated how the environment acts as the selective force, favoring the survival and propagation of individuals possessing the most advantageous traits.

Cras eget sem nec dui volutpat ultrices.

Cras eget sem nec dui volutpat ultrices.

Looking back, the process of natural selection carries a certain inherent clarity and a measure of elegance, despite its unforgiving nature. It possesses a beauty akin to that of a finely balanced mathematical equation. In the concluding remarks of "On the Origin of Species," Darwin himself encapsulates this sentiment:

"There is a grandeur in this view of life, with its several powers, having been originally breathed by the Creator into a few forms or into one: and that, whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being evolved."

The enduring relevance of "On the Origin of Species" manifests in its ongoing contributions to humanity and the environment across diverse fields, from medicine to environmental science. Charles Darwin's motivation for articulating his theory of natural selection parallels the very process itself. Just as a species adapts to its environment, the traits—including the capacity for reasoned analysis, which clearly plays a pivotal role—are refined over time to enhance survival.

0 Comments