Introduction: A Controversial Raid in Bogor

In the early hours of June 23, 2025, a joint task force comprising the Criminal Investigation Unit of the Bogor Police and the Megamendung Police conducted a raid on a private villa in the Puncak area of Bogor Regency, West Java, Indonesia. The operation targeted what authorities described as a “gay party,” resulting in the detention of 75 men for questioning. This incident, which drew significant attention both domestically and internationally, has sparked debates about human rights, privacy, public health, and the legal treatment of LGBTQ+ individuals in Indonesia. The raid, coupled with mandatory health screenings that revealed 30 individuals tested reactive for HIV or syphilis, underscores the complex interplay of cultural norms, legal frameworks, and public health challenges in the world’s largest Muslim-majority country. This article provides a detailed examination of the event, its context, and its far-reaching implications, enriched with historical, cultural, and social perspectives.

The Raid: Details and Immediate Aftermath

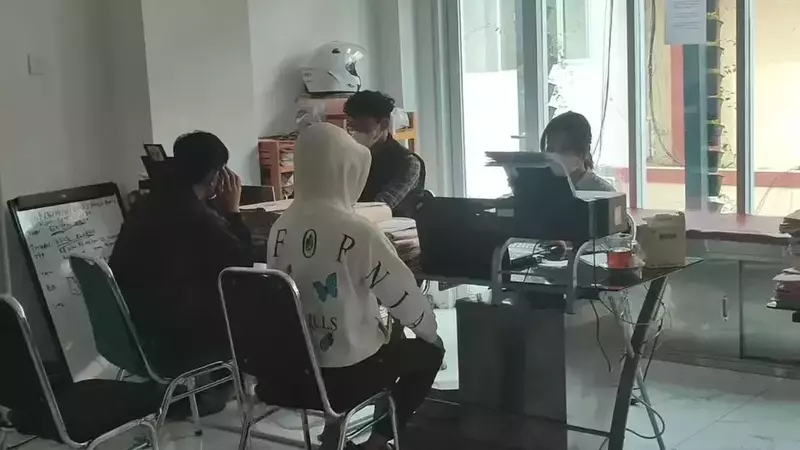

Operation and Detentions

The raid took place at a privately rented villa in the scenic Puncak area, a popular tourist destination known for its cool climate and lush landscapes. According to Teguh Kumara, Head of the Criminal Investigation Unit of Bogor Police, the operation was prompted by public reports of “suspicious activity” at the gathering. The event was initially described by organizers as a “family gathering,” but authorities noted that all participants were male, which fueled their suspicion of homosexual activities. The task force detained all 75 attendees and transported them to Bogor Police Headquarters for questioning.

During the raid, police reported seizing items they deemed as evidence, including four condoms, sex toys, and a decorative sword allegedly used in a dance performance. These items were presented to the media, a practice that human rights advocates argue contributes to public shaming and stigmatization. The police are currently focusing their investigation on four individuals suspected of organizing the event, though no formal charges have been announced as of June 24, 2025.

Health Screenings and Public Health Concerns

Following the detentions, the Bogor Regency Health Office conducted mandatory health screenings, including tests for HIV and syphilis, on all 75 individuals. Dr. Fusia Meidiawaty, Head of the Bogor Regency Health Office, reported that 30 of the participants tested reactive for HIV or syphilis, while 45 tested non-reactive. Dr. Meidiawaty emphasized that a reactive result is not a definitive diagnosis and requires further confirmatory testing at local health centers (puskesmas). She described the screenings as an “early detection effort” aimed at addressing public health risks.

“The results of screening show that 30 people are reactive. It should be underlined that reactive is not necessarily positive. That is only the initial stage. Further examination will be carried out by the puskesmas to determine whether the person concerned has HIV or not,” said Dr. Fusia Meidiawaty.

The public disclosure of these test results has raised significant ethical concerns. Forcing individuals to undergo medical testing without consent and publicizing the outcomes violates international standards for medical privacy and non-discrimination. The World Health Organization (WHO) and UNAIDS have long advocated for voluntary, confidential HIV testing as a cornerstone of effective public health strategies. The Bogor raid’s approach, by contrast, risks deterring individuals from seeking healthcare due to fear of exposure or prosecution.

Legal Context: Indonesia’s Laws and LGBTQ+ Rights

The Legal Landscape for Same-Sex Relationships

Indonesia does not explicitly criminalize consensual same-sex relationships between adults at the national level, except in the province of Aceh, where Sharia law imposes severe penalties, including public flogging or imprisonment for homosexual acts. However, the absence of explicit criminalization does not equate to legal protection. Same-sex couples are ineligible for the legal protections afforded to opposite-sex married couples, and there are no national laws prohibiting discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity.

The 2008 Pornography Law (Law No. 44/2008) has become a primary tool for targeting LGBTQ+ individuals. The law broadly defines “pornography” to include acts deemed “indecent” or contrary to “community morality,” encompassing same-sex sexual activities, oral sex, and anal sex. Violators can face up to 15 years in prison. The vague wording of the law allows authorities significant discretion, enabling them to conduct raids and arrests based on perceived moral violations rather than clear legal breaches.

In December 2022, Indonesia passed a revised Penal Code (Law No. 1/2023), set to take effect in 2026, which criminalizes sex outside of marriage with penalties of up to one year in prison. Since same-sex marriage is not recognized in Indonesia, this provision effectively criminalizes all same-sex sexual conduct. The law applies to both citizens and tourists, raising concerns about its impact on personal freedoms and Indonesia’s tourism industry. Human rights organizations, including Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, have condemned the law as a significant setback for privacy and equality.

“The combination of exploiting the discriminatory pornography law and a lack of accountability for police misconduct has proved to be both dangerous and durable,” said Kyle Knight, senior LGBT rights researcher at Human Rights Watch.

Historical Context of Anti-LGBTQ+ Legislation

The Bogor raid is part of a broader pattern of increasing hostility toward LGBTQ+ individuals in Indonesia, particularly since 2016. That year marked the onset of what Human Rights Watch described as an “anti-LGBT moral panic,” characterized by inflammatory rhetoric from politicians, religious leaders, and public officials. Statements calling for the criminalization of homosexuality, censorship of LGBTQ+ content, and “rehabilitation” through conversion therapy gained traction. In 2016, a mayor publicly warned against instant noodles, claiming they distracted from teaching children “how not to be gay,” illustrating the absurdity of some anti-LGBTQ+ narratives.

In 2017, the Constitutional Court rejected a petition by the Family Love Alliance, a Bogor-based anti-LGBTQ+ coalition, to criminalize all same-sex conduct and extramarital sex. The 5-4 ruling was a narrow victory for human rights advocates, but the issue has since shifted to parliamentary debates over the new Penal Code. The persistence of such proposals reflects deep-seated cultural and religious opposition to non-normative sexual orientations, rooted in Indonesia’s conservative social fabric.

Cultural Context: Religion, Society, and Stigma

Islam and Social Norms in Indonesia

Indonesia is the world’s largest Muslim-majority country, with approximately 86% of its 270 million citizens identifying as Muslim. Islamic teachings, particularly those emphasizing traditional family structures, heavily influence societal attitudes toward sexuality and gender. The Indonesian Ulema Council (MUI), a prominent religious authority, has labeled homosexuality as “deviant” and an affront to “the dignity of Indonesia.” Such pronouncements contribute to widespread stigma, making it difficult for LGBTQ+ individuals to live openly without fear of social or legal repercussions.

Despite Indonesia’s national motto, “Bhinneka Tunggal Ika” (Unity in Diversity), which celebrates its pluralistic heritage, the LGBTQ+ community faces significant exclusion. A 2023 Pew Research Center survey found that 95% of Indonesians oppose same-sex marriage, reflecting entrenched cultural resistance. This opposition is not universal, however; some urban areas, like Jakarta and Yogyakarta, have historically been more tolerant, with discreet LGBTQ+ communities and advocacy groups operating under the radar.

The Role of Religious Organizations

Religious organizations, particularly Nahdlatul Ulama and Muhammadiyah, Indonesia’s two largest Islamic groups, have played a significant role in shaping anti-LGBTQ+ sentiment. Following the Bogor raid, Nahdlatul Ulama leader Ahmad Fahrur Rozi described the event as “disgusting,” while Muhammadiyah’s Anwar Abbas claimed such activities could “lead to the extinction of humankind.” Such rhetoric not only fuels public prejudice but also legitimizes discriminatory actions by authorities. In 2017, West Java police chief Anton Charliyan announced the formation of an anti-LGBTQ+ task force, declaring homosexuality a “disease of the body and soul” that would not be tolerated in the province.

Conversion Therapy and Social Pressure

Conversion therapy, often disguised as “rehabilitation” or religious exorcism, remains a pervasive issue in Indonesia. While a 2020 attempt to legalize conversion therapy through the “Drafted Law of Family Resilience” was rejected by a majority of parliamentary factions, some local governments have de facto legalized such practices. These efforts reflect a broader societal expectation that individuals conform to heterosexual norms, often through marriage. The pressure to marry and uphold traditional family structures is particularly acute in rural areas, where community scrutiny is intense.

Public Health Implications: HIV and Stigma

HIV Prevalence and Testing Controversies

The Bogor raid’s mandatory HIV and syphilis testing has drawn sharp criticism from public health experts and human rights advocates. According to a 2012 Ministry of Health estimate, approximately 5% of Indonesia’s 1 million men who have sex with men (MSM) are living with HIV, a rate significantly higher than the general population. A 2023 Georgetown University study found that MSM in countries with anti-LGBTQ+ laws are five times more likely to be living with HIV, and 12 times more likely in regions where such laws are actively enforced. This correlation highlights how criminalization and stigma deter individuals from accessing testing and treatment.

The public disclosure of the Bogor test results exacerbates these challenges. By associating HIV with perceived moral failings, authorities reinforce stigma, discouraging MSM and other vulnerable groups from seeking care. Human Rights Watch has documented how police raids on private gatherings disrupt HIV outreach efforts, as venues like clubs and saunas often serve as safe spaces for education, counseling, and condom distribution. The closure of such spaces following raids in 2017 and 2018 significantly hampered public health initiatives, contributing to a five-fold increase in HIV rates among MSM since 2007.

“Clubs were hot spots for us because we knew that even the discreet guys felt safe about their sexuality inside, so we could do HIV testing and give condoms and they wouldn’t be scared to participate,” said an HIV outreach worker in Jakarta.

Global Advances in HIV Prevention

While Indonesia grapples with these challenges, global advancements in HIV prevention offer hope. In 2025, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved lenacapavir (marketed as Yeztugo), a long-acting injectable pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) drug that requires only two injections per year. This breakthrough, developed by Gilead Sciences, has shown superior efficacy in preventing HIV transmission compared to oral PrEP. Expanding access to such innovations in Indonesia could significantly reduce HIV rates, but this requires addressing systemic barriers like discrimination and lack of healthcare infrastructure.

Human Rights Violations and International Response

Privacy and Discrimination Concerns

The Bogor raid has been widely condemned as a violation of human rights, particularly the rights to privacy and non-discrimination enshrined in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), to which Indonesia is a signatory. The United Nations Human Rights Committee has emphasized that consensual adult sexual activity in private is protected under the concept of privacy. Amnesty International’s Deputy Director for Indonesia, Wirya Adiwena, described the raid as a “blatant violation of human rights and privacy” that exemplifies the hostile environment for LGBTQ+ individuals in Indonesia.

“This discriminatory raid on a privately rented villa is a blatant violation of human rights and privacy that exemplifies the hostile environment for LGBTI people in Indonesia. This gathering violated no law and posed no threat,” said Wirya Adiwena.

The use of the Pornography Law to justify such raids is particularly troubling. Human Rights Watch has noted that the law’s vague provisions allow authorities to target LGBTQ+ individuals arbitrarily, undermining their rights to association and equal protection under the law. The lack of accountability for police misconduct further perpetuates this cycle of harassment and intimidation.

Global Condemnation and Advocacy

International organizations, including Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and the United Nations, have called for the immediate release of those detained in the Bogor raid and an end to similar operations. These groups urge Indonesia to revise its laws to align with international human rights standards, including repealing discriminatory provisions in the Pornography Law and the new Penal Code. President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo, who in 2016 expressed support for LGBTQ+ rights, has been urged to clarify the prohibition against discriminatory police actions, though his administration has taken little concrete action to address these issues.

Historical Precedents: A Pattern of Persecution

Previous Raids and Their Impact

The Bogor raid is not an isolated incident but part of a disturbing trend. In 2017, police raided a sauna in Jakarta, arresting 141 men, 10 of whom were charged under the Pornography Law. Another raid in Surabaya that year saw 14 men arrested and subjected to non-consensual HIV testing. In 2020, a Jakarta hotel raid resulted in the arrest of nine men, charged with “facilitating obscene acts.” Earlier in 2025, raids on February 1 and May 24 in South Jakarta detained 56 and nine individuals, respectively, under similar pretexts. These operations often involve public shaming, with police displaying condoms and other items to the media as evidence of “immorality.”

In Aceh, where Sharia law applies, the situation is even more severe. In 2017, two men were publicly flogged 83 times each for consensual same-sex relations, watched by thousands. Such punishments, combined with vigilante actions and police raids, create a climate of fear that drives LGBTQ+ individuals underground, limiting their access to community support and healthcare.

The Role of Vigilante Groups

Militant Islamist groups, such as the Islamic Defenders Front, have increasingly collaborated with authorities in targeting LGBTQ+ gatherings. In 2017, vigilantes in Aceh forcibly removed two men from their home, leading to their arrest and flogging. These groups often justify their actions as defending “public morality,” a narrative that resonates with conservative segments of society. The government’s failure to curb such vigilantism exacerbates the vulnerability of LGBTQ+ individuals.

Cultural Enrichment: Music and Resistance

LGBTQ+ Expression Through Music

Despite the challenges, Indonesia’s LGBTQ+ community has found ways to express resilience and identity through cultural mediums like music. In urban centers, underground music scenes have provided safe spaces for self-expression. For example, Yogyakarta’s punk and indie music communities have historically embraced diversity, with bands like Marjinal addressing social justice issues, including discrimination against marginalized groups. Their 2010 song “Marsinah” pays tribute to a labor activist but also resonates with broader themes of resistance against oppression, including for LGBTQ+ individuals.

Internationally, artists like Coldplay have faced backlash in Indonesia for their perceived support of LGBTQ+ rights. In 2023, conservative groups protested Coldplay’s concert in Jakarta, accusing the band of promoting “gay propaganda.” Such incidents highlight the tension between global cultural influences and local conservative values, with music serving as both a battleground and a refuge for marginalized communities.

The Role of Art in Advocacy

Art and music have long been tools for advocacy in Indonesia. The 2019 film “Memories of My Body,” directed by Garin Nugroho, tells the story of a young dancer navigating gender and sexual identity in rural Java. Despite facing censorship, the film sparked discussions about acceptance and diversity. Similarly, drag performances and underground cabarets in Jakarta offer spaces for self-expression, though they often operate in secrecy to avoid police raids. These cultural expressions underscore the resilience of Indonesia’s LGBTQ+ community in the face of systemic oppression.

Conclusion: A Call for Change

The raid on the private gathering in Bogor on June 23, 2025, is a stark reminder of the challenges faced by Indonesia’s LGBTQ+ community. The detention of 75 men, the forced health screenings, and the potential for prosecution under vague morality laws highlight the intersection of legal, cultural, and public health issues. While Indonesia’s diverse cultural heritage and progressive urban pockets offer hope for change, the dominance of conservative religious and social norms continues to marginalize sexual and gender minorities.

Addressing these challenges requires multifaceted action: revising discriminatory laws, ensuring police accountability, protecting medical privacy, and fostering societal acceptance through education and cultural dialogue. International pressure and local advocacy will be crucial in pushing for reforms that align with Indonesia’s international human rights obligations. Until then, events like the Bogor raid will continue to cast a shadow over the country’s commitment to “Unity in Diversity,” leaving its LGBTQ+ citizens in a precarious struggle for dignity and equality.

0 Comments