In an era where the rights and historical narratives of LGBTQ+ Americans face significant challenges, the Ohio Lesbian Archives (OLA) in Cincinnati stands as a resilient testament to the power of community-driven preservation. Founded in 1989, this unique institution has been meticulously collecting and safeguarding materials that document the lives, struggles, and triumphs of the lesbian and broader LGBTQ+ community in Cincinnati and beyond. With the recent political shifts threatening to erase marginalized histories, the OLA’s mission to ensure queer visibility has never been more critical. This expanded exploration delves into the archives’ origins, its cultural and historical significance, the challenges it faces, and its enduring role in preserving a legacy of resilience and identity.

Origins of the Ohio Lesbian Archives

A Friendship Forged in Secrecy

The Ohio Lesbian Archives was born from the deep bond between Phebe Beiser and Victoria “Vic” Ramstetter, two women who met in the 1970s as self-described “hidden, secret, teenage lesbians.” Growing up in Cincinnati, a city steeped in conservative values at the time, they found solace in their shared experiences. The lack of visible gay role models in their youth fueled their determination to create a space where queer identities could be celebrated and preserved. Beiser, now in her mid-70s, recalls their mantra: “We never wanted to be invisible again.” This commitment to visibility became the cornerstone of the OLA’s mission.

In their 20s, Beiser and Ramstetter lived together in group houses in Cincinnati’s Clifton neighborhood, humorously referring to their time there as “surviving the lesbian commune.” These communal living spaces were more than homes; they were hubs of activism and creativity, where young, idealistic lesbians gathered to envision a world where their identities were not only accepted but celebrated. Their shared vision of turning activism into something “fun and interesting” laid the groundwork for a legacy that would span decades.

The Crazy Ladies Bookstore: A Cultural Hub

In 1979, the opening of the Crazy Ladies Bookstore in Cincinnati’s Northside neighborhood marked a pivotal moment for the local lesbian community. Named to reclaim the narrative of women dismissed by history as “crazy,” the bookstore became a cultural and social epicenter. Women flocked to the space, purchasing homes in the surrounding area and gathering for coffee, tea, and conversations about feminism, lesbian identity, and social change. The bookstore was more than a retail space; it was a sanctuary where ideas flourished and community thrived.

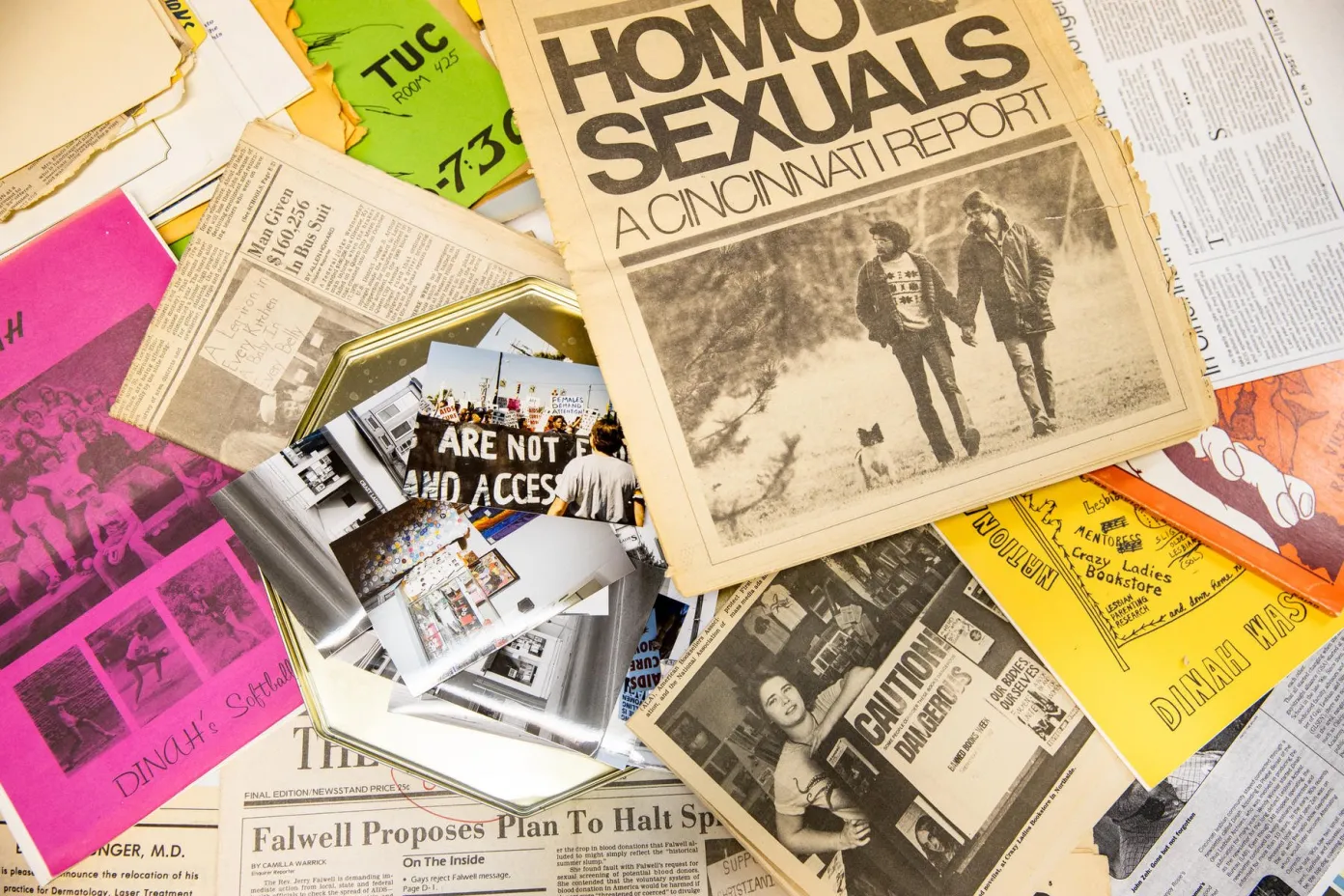

In 1989, Beiser and Ramstetter established the Ohio Lesbian Archives on an upper floor of the Crazy Ladies Bookstore. This small room became a repository for a growing collection of ephemera—books, newsletters, photographs, and more—that documented the lesbian experience in Cincinnati and beyond. The archives’ founding was a direct response to the realization that mainstream institutions were unlikely to preserve queer histories. As Beiser noted, “We held on to them because we knew they could not be replaced. It’s proof of our existence.”

“We never wanted to be invisible again.” — Phebe Beiser

The Cultural and Historical Significance of the OLA

Preserving a Marginalized Narrative

The Ohio Lesbian Archives is one of only a handful of lesbian-focused archives in the United States, making it a rare and vital resource. Its collection spans decades, offering an intimate lens into the lives of queer women and the broader LGBTQ+ community. From personal diaries to political buttons, the archives house a diverse array of materials that tell stories of pride, struggle, and resilience. Notable items include an AIDS memorial quilt, a 1940s scrapbook from a local woman who played for a professional women’s softball team, and every issue of Dinah, a lesbian feminist newsletter published from the 1970s to the 1990s.

Dinah, named playfully as a nod to the National Organization for Women’s Task Force on Sexuality and Lesbianism (which the editors jokingly called “FOSAL” or “fossil”), was a cornerstone of the archives’ early collection. The newsletter served as a vital communication tool for the lesbian community, sharing news of events, activism, and personal stories. A 1991 issue featured letters from readers, including one from a woman homesteading with her partner and another expressing frustration at the lack of legal protections for LGBTQ+ individuals fired for their sexual orientation. These artifacts capture the raw emotions and challenges of the time, providing a window into a community fighting for recognition.

A Reflection of Community and Identity

The OLA’s collection is more than a historical record; it is a mirror reflecting the diverse ways queer individuals have navigated the world. As Nancy Yerian, the archives’ board president, explains, “Many people who are coming to the archives are looking for a reflection of themselves and in many ways that’s why Vic and Phebe started it. It shows models of ways to be in the world and a feeling of not being alone and not being the first queer person or lesbian.”

The archives’ materials, ranging from Pride march buttons to VHS copies of The L Word, offer tangible connections to the past. A particularly poignant item is a button bearing the word “REMEMBER” alongside an inverted pink triangle, a symbol reclaimed from its use by the Nazis to identify gay and transgender individuals. Such artifacts underscore the resilience of a community that has faced persecution yet continues to assert its right to exist.

Musical Context: The Women’s Music Movement

The OLA’s collection also captures the influence of the women’s music movement, a cultural phenomenon of the 1970s and 1980s that empowered lesbian and feminist communities. Artists like Cris Williamson, Holly Near, and Margie Adam performed at festivals and venues across the country, including Cincinnati, where Beiser interviewed them for Dinah. These performances were not just concerts but acts of resistance, creating spaces where women could celebrate their identities openly. The archives preserve posters, flyers, and recordings from these events, documenting a vibrant subculture that challenged mainstream norms and fostered community pride.

Challenges to Preservation: The Impact of Political Shifts

The Marking Diverse Ohio Program

In 2023, the Ohio History Connection launched the Marking Diverse Ohio program, a three-year initiative to diversify the state’s historical markers by including ten new stories of LGBTQ+ Ohioans. Funded by a $250,000 grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS), the program aimed to address the underrepresentation of queer narratives among Ohio’s 1,800 historical markers. The Ohio Lesbian Archives and the Crazy Ladies Bookstore were selected for a joint marker, a recognition that promised to cement their place in the state’s historical record.

Preparations for the marker were nearly complete, with a location secured in a city park near the former bookstore site and oral histories recorded with Beiser and Ramstetter. The installation was slated for June 2023, coinciding with Pride Month. However, the project faced a significant setback when the Trump administration issued an executive order in March 2025 targeting federal agencies, including the IMLS, for elimination. The Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) canceled $25 million in IMLS grants, including the funding for the Marking Diverse Ohio program. The IMLS’s final social media post listed the LGBTQ+ historical markers as an example of “government excess,” highlighting the political motivations behind the cuts.

Broader Implications for Cultural Institutions

The cancellation of IMLS funding had far-reaching consequences beyond the OLA. In Ohio, institutions like the Cincinnati Zoo, Dayton Metro Library, and the Contemporary Arts Center lost funding for critical programs. Nationally, museums and libraries faced economic upheaval, with projects like the digitization of rare manuscripts at The Rosenbach museum in Pennsylvania and renovations at the Woodmere Art Museum at risk. The American Library Association and the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees filed a lawsuit against the Trump administration, arguing that libraries and museums are essential to preserving collective history. As ALA President Cindy Hohl stated, “Libraries play an important role in our democracy, from preserving history to … offering access to a variety of perspectives.”

Despite a federal judge’s ruling allowing the dismantling of the IMLS to continue, the OLA remains undeterred. The cost to install the marker for the archives and bookstore is estimated at $3,000–$5,000, a sum the volunteer-run organization is now seeking through community foundations and other sources. This resilience reflects the queer community’s long history of self-reliance in the face of systemic exclusion.

The OLA’s Evolution and Community Impact

A DIY Endeavor

From its inception, the Ohio Lesbian Archives has been a grassroots effort, powered by dedicated volunteers. When the Crazy Ladies Bookstore’s founder, Carolyn Dellenbach, left Cincinnati, the bookstore transitioned into a feminist collective, with patrons taking on its operation. Similarly, the OLA has relied on the passion of individuals like Beiser, Ramstetter, and newer volunteers like Lüdi Rich and Nancy Yerian. Rich, a 27-year-old librarian, discovered the archives after moving to Cincinnati and seeking queer community spaces. Inspired by a panel featuring Beiser, she began volunteering and has since become a key contributor to the archives’ work.

Yerian, who returned to Cincinnati after college, found in the OLA a sense of hope and belonging. “Finding the Archives and the people I’ve met through the organization and the community we’re creating, as well as the history we’re preserving — it gave me a lot of hope that I could create a life for myself here,” she said. The archives’ open hours, held twice weekly, welcome researchers, students, and curious visitors, fostering a sense of connection and continuity.

Digitization and Accessibility

The OLA has embraced modern technology to make its collection more accessible. Volunteers have digitized photographs, now part of a collection at the Cincinnati Public Library, and are working to archive other materials. The archives’ relocation in 2023 to a larger space at the eCenter in Over-the-Rhine, across from Washington Park, has allowed for greater visibility and community engagement. The new location, a significant upgrade from the cramped, moldy basement of the Clifton United Methodist Church where the archives resided from 2006 to 2023, reflects the organization’s growth and ambition.

Community Building and Future Plans

Beyond preservation, the OLA serves as a hub for community building. It hosts events, film screenings, and discussions, both virtual and in-person, to educate the public about LGBTQ+ history. The organization is also forging partnerships, such as with the Cincinnati Public Library, to expand its reach through exhibitions and lectures. Volunteers are actively sought to assist with tasks like filing, sorting, and organizing, with a particular influx of younger Cincinnatians eager to contribute.

The OLA’s future plans include expanding into a dedicated space where it can host talks and create a more comfortable learning environment. This vision aligns with its original mission to ensure that lesbian and queer stories are not only preserved but celebrated. As Beiser reflects, “There are few places in the world—and nowhere in the region—where I can see myself, my LGBTQ family, and feel so empowered.”

LGBTQ+ Rights in Ohio: A Historical Context

Legal Milestones and Ongoing Struggles

The history of LGBTQ+ rights in Ohio mirrors the national struggle for equality. Same-sex sexual activity was legalized in Ohio in 1974, and same-sex marriage became legal in 2015 following the Supreme Court’s ruling in Obergefell v. Hodges, a case originating in Ohio. The 2020 Bostock v. Clayton County decision extended employment protections to LGBTQ+ individuals, but recent efforts by the Trump administration’s Equal Employment Opportunity Commission to curtail these protections highlight the fragility of these gains.

Ohio’s legal landscape has been a patchwork of progress and setbacks. While cities like Cincinnati, Columbus, and Dayton have passed anti-discrimination ordinances, the state lacks comprehensive protections against discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity. The OLA’s collection, including posters reminding Ohioans of the lack of employment protections pre-Bostock, underscores the community’s long fight for equality.

Cincinnati’s Role in Queer Activism

Cincinnati has a rich history of queer activism, with the OLA playing a central role. The city’s first Pride parade in April 1973, where Beiser and others marched, marked a bold assertion of visibility in a conservative region. The Crazy Ladies Bookstore and the OLA became focal points for organizing, with events like potlucks, dances, and rallies documented in the archives’ flyers and newsletters. These materials capture a community that, despite facing hostility, built networks of support and resistance.

Conclusion: A Legacy of Resilience

The Ohio Lesbian Archives stands as a powerful symbol of resilience and self-determination. In the face of political efforts to erase queer history, the archives continue to preserve the stories of those who have fought for their place in the world. From its humble beginnings above the Crazy Ladies Bookstore to its current home in Over-the-Rhine, the OLA has grown into a vital resource for researchers, students, and community members seeking to understand and celebrate queer history.

The archives’ work is a reminder that history is not just recorded but actively shaped by those who refuse to be silenced. As Lüdi Rich poignantly states, “It really is just us, preserving our history.” Whether through a historical marker or the ongoing efforts of its volunteers, the Ohio Lesbian Archives ensures that the legacy of Cincinnati’s LGBTQ+ community remains visible, vibrant, and enduring.

“It really is just us, preserving our history.” — Lüdi Rich

0 Comments