The global response to HIV/AIDS has been a story of remarkable progress intertwined with persistent challenges. Despite decades of scientific advancements, international collaboration, and community-driven efforts, the fight to end AIDS as a public health threat by 2030 faces unprecedented setbacks. A recent report by the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) highlights a troubling rise in criminalization targeting high-risk groups, coupled with drastic cuts in U.S. funding, which together threaten to unravel years of progress. This article explores the complexities of the current global HIV/AIDS landscape, delving into the impact of punitive laws, funding disruptions, and the resilience of communities striving to maintain momentum toward ending the epidemic. By examining historical, cultural, and societal contexts, we aim to provide a comprehensive understanding of the crisis and the urgent need for transformative action.

The Global HIV/AIDS Epidemic: A Historical Perspective

The HIV/AIDS epidemic, first identified in the early 1980s, has left an indelible mark on global health, claiming over 44.1 million lives by 2024. Initially shrouded in stigma and misunderstanding, the epidemic spurred a global movement that combined scientific innovation, activism, and policy reform to address its devastating impact. By 2024, approximately 40.8 million people were living with HIV globally, with sub-Saharan Africa bearing the heaviest burden, accounting for over 25.9 million cases—more than two-thirds of the global total. The region’s high prevalence is attributed to a combination of biological, social, and structural factors, including limited healthcare access, gender inequalities, and cultural practices that increase transmission risks.

In the early years, the lack of effective treatments and widespread discrimination fueled fear and misinformation. The 1983 Denver Principles, a landmark manifesto by people living with HIV/AIDS, called for dignity, inclusion, and self-empowerment, laying the foundation for community-led responses. Over the decades, advancements such as antiretroviral therapy (ART) and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) transformed HIV from a death sentence to a manageable chronic condition for many. By 2024, 31.6 million people were accessing ART, a significant increase from 7.7 million in 2010, contributing to a 58% decline in AIDS-related deaths among women and girls and a 50% decline among men and boys since 2010.

Despite these gains, disparities persist. Sub-Saharan Africa has seen a 56% reduction in new HIV infections since 2010, while regions like the Middle East and North Africa have experienced a 94% increase. These regional variations underscore the uneven progress in the global response, influenced by differences in healthcare infrastructure, funding, and social attitudes toward marginalized groups.

Rising Criminalization: A Barrier to HIV Prevention and Care

Punitive Laws Targeting Key Populations

UNAIDS defines "key populations" as groups disproportionately affected by HIV, including gay men and other men who have sex with men (MSM), sex workers, transgender individuals, people who inject drugs, and those in prisons or other enclosed settings. These groups face heightened risks due to social, legal, and structural barriers that limit their access to healthcare and prevention services. In 2024, HIV prevalence among gay men was 7.6%, significantly higher than the global adult prevalence of 0.7%. Sex workers are seven times more likely to live with HIV than the general population, and transgender individuals face similarly elevated risks.

For the first time in a decade, the number of countries criminalizing same-sex sexual activity and gender expression has increased, reversing a trend toward decriminalization. In 2025, only eight of 193 countries worldwide refrained from criminalizing key populations or behaviors such as non-disclosure of HIV status, exposure, or transmission. This resurgence of punitive laws has profound implications for HIV prevention and treatment, as fear of prosecution drives vulnerable groups away from essential services.

In Mali, recent legislation has criminalized homosexuality, expanding from previous laws that only banned “public indecency.” Transgender individuals now face explicit criminalization, further marginalizing an already vulnerable group. Similarly, Trinidad and Tobago’s Court of Appeal overturned a 2018 ruling that decriminalized consensual same-sex relations, reinstating a colonial-era ban. In Uganda, the 2023 Anti-Homosexuality Act has intensified penalties for same-sex relations, creating a climate of fear and hostility. Ghana has also reintroduced legislation that would impose harsher sentences for gay sex, threatening to undo years of advocacy for equality.

These laws are not merely legal restrictions; they have tangible public health consequences. A study in sub-Saharan Africa found that HIV prevalence among MSM was five times higher in countries with criminalizing laws compared to those without. Criminalization fosters stigma, discrimination, and violence, deterring individuals from seeking HIV testing, treatment, or prevention services. For example, gay men in criminalizing countries are twice as likely to avoid HIV testing due to fear of harassment or arrest.

Case Studies: Uganda, Ghana, Mali, and Trinidad and Tobago

Uganda: The 2023 Anti-Homosexuality Act, often referred to as the “Kill the Gays” bill, has drawn international condemnation for its severe penalties, including life imprisonment and, in some cases, the death penalty for same-sex conduct. This legislation has led to increased violence against LGBTQ+ individuals and forced many to flee the country or go underground. Community clinics that once provided safe spaces for HIV testing and PrEP distribution have faced closures or harassment, severely limiting access for MSM and other key populations.

Ghana: The reintroduction of anti-gay legislation in Ghana has sparked alarm among activists. The proposed bill would increase penalties for same-sex activities and criminalize advocacy for LGBTQ+ rights, further isolating key populations. This legislative shift threatens Ghana’s progress in reducing HIV prevalence, as community-led organizations, which rely heavily on donor funding, face operational challenges.

Mali: Mali’s recent criminalization of homosexuality and transgender identity marks a significant regression. Previously, vague laws against “public indecency” were used to target LGBTQ+ individuals, but the new explicit bans exacerbate the risks for these communities. The lack of legal protections and increasing social hostility make it nearly impossible for transgender individuals and MSM to access HIV services without fear of persecution.

Trinidad and Tobago: The reinstatement of colonial-era laws banning same-sex relations in Trinidad and Tobago represents a setback for a region that had seen progress in decriminalization. The 2018 ruling that struck down these laws was a landmark victory for LGBTQ+ rights, but its reversal has reintroduced barriers to healthcare access, particularly for MSM, who are already at higher risk of HIV infection.

The Impact of U.S. Funding Cuts

The Role of PEPFAR and Its Abrupt Halt

The U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), launched in 2003, has been a cornerstone of the global HIV/AIDS response, saving an estimated 26.9 million lives through treatment and prevention programs. In 2024, PEPFAR reached 2.3 million adolescent girls and young women with comprehensive HIV prevention services and enabled 2.5 million people to access PrEP. However, in January 2025, the Trump administration announced a 90-day freeze on U.S. foreign aid, including PEPFAR funding, which accounted for approximately 73% of global donor funding for HIV programs. This sudden withdrawal has had a seismic impact, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, where PEPFAR funded nearly 45% of HIV prevention programs.

Countries like Malawi (88.5%), Zimbabwe (82.7%), and Mozambique (81.8%) were almost entirely dependent on PEPFAR for their prevention efforts. The funding freeze led to immediate disruptions, including the closure of community clinics, suspension of prevention programs like condom distribution and voluntary medical male circumcision (VMMC), and layoffs of community health workers. In Nigeria, the number of people receiving PrEP dropped from 43,000 in November 2024 to fewer than 6,000 by April 2025, illustrating the scale of the crisis.

UNAIDS modeling projects dire consequences if PEPFAR funding is not restored. By 2029, an additional 6 million new HIV infections and 4 million AIDS-related deaths could occur globally. In sub-Saharan Africa, a one-year halt in funding for preventive drugs could result in 700,000 people losing access to PrEP, leading to approximately 10,000 additional HIV cases over five years, according to Bristol University estimates.

Personal Stories: The Human Toll

The funding cuts have had a profound impact on individuals like Mosele Mothibi, an HIV-positive unemployed garment worker from Maseru, Lesotho. After USAID funding was reduced, Mothibi’s access to medications was curtailed, forcing her to ration her ART doses. This not only jeopardizes her health but also increases the risk of viral rebound, which could lead to further transmission. Mothibi’s story is emblematic of millions who rely on donor-funded clinics for life-saving services, particularly in low-income countries where domestic resources are insufficient to fill the gap.

“I felt suffocated, like being choked… It was like a volcano came and took everything away. It felt like a death penalty,” said Nombeko Mpongo, a longtime HIV activist in Cape Town, reflecting on the funding cuts.

Mpongo’s response highlights the emotional and psychological toll of the crisis, as communities grapple with the loss of services they fought hard to establish. Her determination to rally and fight back underscores the resilience of community-led organizations, which have been critical to the HIV response.

Regional Disparities and Challenges

Sub-Saharan Africa: Progress and Peril

Sub-Saharan Africa remains the epicenter of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, with 25.9 million people living with HIV in 2023. Despite significant progress—a 56% reduction in new infections since 2010—the region faces unique challenges. Adolescent girls and young women (AGYW) aged 15–24 are three times more likely to acquire HIV than their male counterparts, driven by gender-based violence, lack of education, and economic dependence. Programs like PEPFAR’s DREAMS initiative, which provided comprehensive prevention services to 2 million AGYW, have been halted, exacerbating vulnerabilities.

Countries like Botswana, Eswatini, Rwanda, Tanzania, and Zimbabwe have achieved the UNAIDS “95-95-95” targets: 95% of people living with HIV knowing their status, 95% of those diagnosed receiving ART, and 95% of those on treatment achieving viral suppression. However, the funding cuts threaten to erode these gains, particularly in high-burden countries like South Africa, which hosts 7.7 million people living with HIV, the highest globally.

Middle East and North Africa: Rising Infections

In contrast to sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) have seen a 94% increase in new HIV infections since 2010. This alarming trend is driven by limited access to prevention services, widespread stigma, and punitive laws targeting key populations. In many MENA countries, cultural and religious norms exacerbate discrimination against MSM, sex workers, and transgender individuals, making it difficult to implement effective HIV programs. The lack of domestic funding and reliance on international donors further complicates the response in this region.

Scientific Advances and the Path Forward

Innovations in HIV Prevention

Despite the challenges, scientific advancements offer hope. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s approval of long-acting injectable lenacapavir in June 2025 represents a breakthrough in HIV prevention. Administered every six months, lenacapavir could significantly improve adherence compared to daily oral PrEP. Experts estimate that generic versions could cost as low as $25–$46 per person per year with sufficient demand, making it a cost-effective option for low-income countries.

Other innovations, such as twice-yearly injectable PrEP and improved ART regimens, have bolstered the global response. However, access to these tools remains limited, particularly for key populations who face barriers due to criminalization and stigma. Ensuring equitable distribution of these advancements is critical to achieving the 2030 goal of ending AIDS as a public health threat.

Community Resilience and Domestic Funding

In the face of funding cuts, some countries have demonstrated resilience by increasing domestic HIV budgets. South Africa, which funds 77% of its AIDS response, has committed to a 5.9% annual increase in health expenditure through 2028, including a 3.3% increase for HIV and tuberculosis programs. Twenty-five of the 60 low- and middle-income countries surveyed by UNAIDS plan to boost domestic HIV funding by 8% by 2026, amounting to an additional $180 million.

“This is the future of the HIV response—nationally owned and led, sustainable, inclusive, and multisectoral,” said Winnie Byanyima, UNAIDS Executive Director.

Community-led organizations remain at the forefront, serving as advocates, educators, and care providers. However, over 60% of women-led HIV organizations reported funding losses or service suspensions in early 2025, highlighting the urgent need for sustained support.

Cultural and Social Contexts

The HIV/AIDS epidemic is deeply intertwined with cultural and social dynamics. In sub-Saharan Africa, practices like concurrency—multiple concurrent sexual partners—contribute to high transmission rates. Gender norms that limit women’s ability to negotiate safe sex or refuse unwanted advances exacerbate risks, particularly for AGYW. In South Africa, a 2005 study found that 28% of young males and 27% of young females believed a girl did not have the right to refuse sex with her boyfriend, reflecting entrenched power imbalances.

In the MENA region, conservative cultural attitudes and religious prohibitions create additional barriers. Homosexuality and gender nonconformity are often taboo, driving key populations underground and away from healthcare. Community-led initiatives, such as safe clinics in Côte d’Ivoire for LGBTQ+ individuals, have shown promise in overcoming these barriers, but their sustainability is threatened by funding cuts.

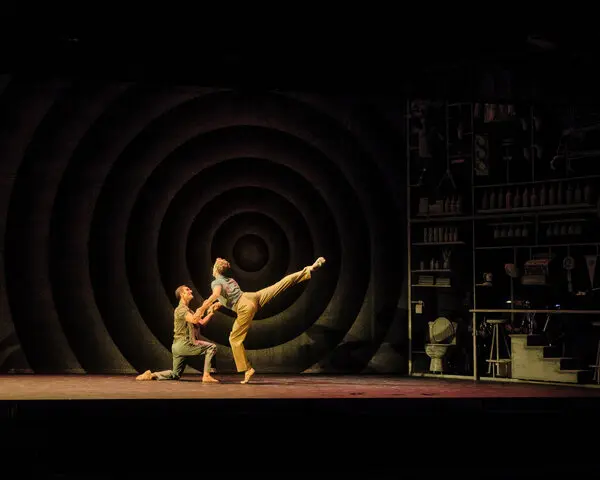

Music and art have also played a significant role in HIV/AIDS advocacy. In the 1980s and 1990s, musicians like Freddie Mercury, whose death from AIDS-related causes in 1991 raised global awareness, and campaigns like “46664” led by Nelson Mandela, used music to destigmatize the disease and raise funds. In Africa, artists like Yvonne Chaka Chaka have supported HIV education through their platforms, emphasizing the power of cultural icons in shaping public perceptions.

The Road to 2030: Challenges and Opportunities

The UNAIDS 2030 targets aim to reduce new HIV infections and AIDS-related deaths by 90% from 2010 levels. While progress has been made—new infections dropped from 2.1 million in 2010 to 1.3 million in 2024, and deaths fell from 1.4 million to 630,000—the current trajectory suggests the world is off track. The funding crisis, rising criminalization, and humanitarian challenges like climate shocks and conflict further complicate the path forward.

UNAIDS emphasizes the need for global solidarity, increased domestic funding, and the removal of legal and social barriers. Decriminalizing key populations, expanding access to prevention tools like PrEP, and integrating HIV services into universal health coverage are critical steps. The upcoming International AIDS Society conference in Kigali, Rwanda, from July 13–17, 2025, will provide a platform to discuss these challenges and share strategies for resilience.

The global HIV/AIDS response stands at a crossroads. The tools and knowledge to end the epidemic exist, but political will, financial commitment, and social transformation are essential to overcome the current crisis. As Winnie Byanyima stated, “Together, we can still end AIDS as a public health threat by 2030—if we act with urgency, unity, and unwavering commitment.”

0 Comments