The Crack of the Bat, the Slap of the Hand

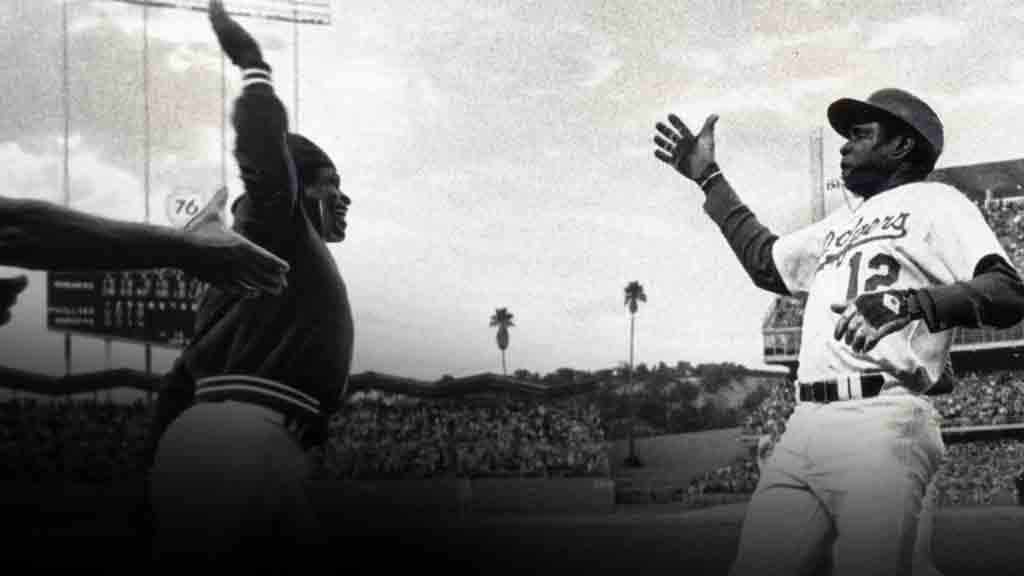

In the electric haze of a 1977 Los Angeles Dodgers game, something wild and beautiful was born. It wasn’t just the crack of Dusty Baker’s bat as he smashed his 30th home run of the season, sending the crowd into a frenzy. It was what happened next, on October 2, at Dodger Stadium, when Glenn Burke—outfielder, dreamer, and the first openly gay Major League Baseball player—ran onto the field, his arm thrust high, his body pulsing with joy. Baker, jogging back from third base, didn’t hesitate. He slapped Burke’s hand, and the high five was born. A gesture so simple, so raw, so defiantly alive that it would ripple through sports, nightlife, and queer culture, becoming a universal symbol of celebration, connection, and unapologetic pride. This was Glenn Burke’s gift to the world—a spark of queer genius that still burns bright.

(But Burke’s story is more than a single slap of palms. It’s a tale of radical love, unyielding authenticity, and a life lived at the intersections of Blackness, queerness, and athletic prowess. It’s about a man who dared to be himself in a world that wasn’t ready, whose legacy pulses through every high five exchanged in a sweaty club, a packed stadium, or a quiet moment of solidarity between lovers. This is a story of glamour, grit, and the kind of erotic defiance that makes history. So, let’s dive into the life of Glenn Burke, the high five’s unsung hero, and explore how his queer swagger reshaped culture in ways we’re still feeling today.

The Soul of the Clubhouse

Glenn Burke was a force—six feet of charisma, with biceps that earned him the nickname “King Kong” and a smile that could light up the Castro. Born in Oakland, California, in 1952, he was a multi-sport phenom, dominating basketball courts at Berkeley High School with a perfect season and a state championship in 1970. But baseball was his true love, and by 1972, the Los Angeles Dodgers had drafted him, seeing in him the potential to be “the next Willie Mays.”

(Burke wasn’t just a player; he was the soul of the Dodgers’ clubhouse. His humor, his energy, his red jockstrap—a bold sartorial choice in an era of plain white briefs—made him unforgettable. He was out to his teammates, a rarity in the hyper-macho world of 1970s baseball. Some, like team captain Davey Lopes, embraced him, saying, “No one cared about his lifestyle.” Others, like Dodgers GM Al Campanis, weren’t so kind, offering Burke a $75,000 bonus to marry a woman. Burke’s response? “I guess you mean to a woman.” That quip, dripping with wit and defiance, was pure queer fire.

(Imagine him in that clubhouse, his laughter echoing, his body moving with the kind of confidence that comes from knowing who you are, even when the world tells you to hide. There’s something undeniably sexy about that—Burke’s refusal to dim his light, his insistence on living as a Black gay man in a space that demanded conformity. It’s the same energy you feel in a queer nightclub when the DJ drops a Donna Summer track, and the crowd loses itself in a sea of sweat and sequins. Burke was that spark, that pulse, that unapologetic yes.

A Love Story in the Shadows

Burke’s queerness wasn’t just a personal truth; it was a radical act. Rumors swirled about his friendship with Tommy Lasorda Jr., the openly gay son of Dodgers manager Tommy Lasorda. The elder Lasorda, a baseball legend, was in denial about his son’s sexuality, and Burke’s presence—his easy camaraderie with “Spunky”—was a threat. The whispers of their relationship, whether platonic or romantic, added fuel to the fire of prejudice that would soon engulf Burke’s career.

(Picture it: two young men, one a rising star, the other a rebel in a world of pinstripes, finding solace in each other’s company. There’s an erotic undercurrent here, not in the explicit sense, but in the intimacy of shared secrets, stolen glances, and the thrill of being seen. In a sport that fetishized stoicism, Burke and Lasorda Jr. were a quiet rebellion, their bond a middle finger to the status quo. It’s the kind of love story that feels like a grainy Polaroid from a 1970s gay bar—hazy, dangerous, and achingly beautiful.

The High Five: A Queer Anthem in Motion

Let’s talk about that high five. October 2, 1977, was a day of triumph. Dusty Baker’s home run wasn’t just a personal milestone; it made the Dodgers the first team in MLB history to have four players hit 30 or more home runs in a season. As Baker rounded the bases, Burke, waiting on deck, raised his hand high, his body arched back in a pose that was equal parts athletic and campy. Baker, caught up in the moment, slapped it. The crowd roared, but it was that simple gesture—two hands meeting in midair—that stole the show.

(Burke didn’t stop there. After hitting his own home run later in the game, he returned to the dugout, and Baker gave him the second-ever high five. It was a moment of pure, unscripted joy, a physical manifestation of camaraderie that transcended the game. But what makes this story deliciously queer is what happened next. Burke, now a fixture in San Francisco’s Castro district, brought the high five to the gay community. He’d sit on the hood of a car outside the Pendulum Club, flashing that magnetic smile, high-fiving passersby. The gesture became a “defiant symbol of gay pride,” as writer Michael J. Smith put it in a 1982 Inside Sports article.

(Think about that: a Black gay man, in the heart of the Castro, turning a sports ritual into a queer anthem. The high five was no longer just about victory on the field; it was about survival, solidarity, and the electric thrill of connection. It’s the same energy you feel when you lock eyes with a stranger on the dancefloor, their body moving to the beat of Sylvester’s “You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real),” and you know, without words, that you’re part of something bigger. Burke’s high five was a love letter to the queer community, a gesture that said, We’re here, we’re fabulous, and we’re not going anywhere.

(From Castro to Cosmos

The high five’s journey from Dodger Stadium to the global stage is a masterclass in queer influence on pop culture. By the early 1980s, it had spread beyond sports, infiltrating music videos, TV shows, and, yes, the sweaty, glitter-dusted world of queer nightlife. Imagine a drag queen in a sequined gown, mid-performance, pausing to high-five the front row. Or two lovers, fresh from a night of cruising, slapping hands as they laugh their way home. The high five became a universal language, but its roots are unmistakably queer, Black, and rebellious.

(It’s no surprise that the gesture took off in the Castro, a neighborhood that was, in the late 1970s, a pulsing epicenter of gay liberation. Harvey Milk had just been elected to the San Francisco Board of Supervisors, the first openly gay elected official in California, and the air was thick with possibility. Burke, with his athletic swagger and unapologetic joy, fit right in. He wasn’t just a baseball player; he was a cultural alchemist, turning a moment of sports camaraderie into a symbol of queer resilience. As RuPaul might say, “You better work!”—and Burke did, leaving a legacy that’s as campy as it is profound.

The Cost of Being Out

But Burke’s story isn’t all glitter and high fives. The price of his authenticity was steep. In 1978, the Dodgers traded him to the Oakland Athletics, a move many teammates believed was driven by homophobia. Dusty Baker later recalled a conversation with the team trainer: “I said, ‘Why’d they trade Glenn? He was one of our top prospects.’ He said, ‘They don’t want any gays on the team.’”

(In Oakland, things got worse. Manager Billy Martin introduced Burke to the team with a slur, calling him a “faggot” in front of his new teammates. A knee injury in spring training gave Martin an excuse to demote Burke to the minors, and by 1980, at just 27, Burke’s professional baseball career was over. “Prejudice drove me out of baseball sooner than I should have,” he told The New York Times. “But I wasn’t changing.”

(Burke’s defiance is heartbreaking and sexy in its rawness. There’s something fiercely erotic about a man who refuses to bend, who stands tall in his truth even as the world tries to break him. It’s the same energy you see in the ballroom scene, where voguers strike poses with a ferocity that dares anyone to challenge their existence. Burke was voguing in his own way, his red jockstrap and high fives a declaration of self-love in a world that offered him little.

(A Life After Baseball

Retiring from baseball, Burke found a new home in the Castro, where he became a local legend. He competed in the 1982 and 1986 Gay Games, winning medals in track and basketball, and dominated the San Francisco Gay Softball League as a star third baseman. But life wasn’t easy. A 1987 car accident crushed his leg, ending his athletic career and plunging him into a spiral of drug addiction and homelessness. By 1993, he was diagnosed with HIV, and on May 30, 1995, he died of AIDS-related complications at 42.

(Yet even in his darkest moments, Burke remained a beacon. His sister, Lutha Davis, recalled, “Now when something great happens in life, people do the high five. I call it ‘the high five of life.’” The Oakland A’s, to their credit, provided financial support after his diagnosis went public, and in 2013, Burke was inducted into the National Gay and Lesbian Sports Hall of Fame. Major League Baseball honored him at the 2014 All-Star Game, though Fox’s broadcast notably omitted any mention of him.

(Burke’s life was a testament to the queer art of survival. He once told People magazine, “My mission as a gay ballplayer was to break a stereotype. I think it worked.” His story is a reminder that joy and pain often coexist, that the same man who invented the high five also faced unimaginable prejudice. It’s a narrative that resonates with anyone who’s ever felt the sting of rejection but kept dancing anyway.

(The High Five’s Lasting Swagger

Today, the high five is everywhere—from sports arenas to corporate boardrooms to queer dancefloors. It’s been referenced in everything from Seinfeld episodes to Beyoncé’s “Single Ladies” video, where the hand choreography feels like a distant cousin of Burke’s gesture. But its queer roots are often forgotten, buried under layers of mainstream assimilation. That’s why telling Burke’s story matters. It’s a reclaiming of a legacy, a reminder that the things we take for granted often come from the margins, from the Black and queer bodies that dared to dream bigger.

(There’s something inherently sensual about the high five—a quick, electric connection, a meeting of skin that says, I see you, I feel you, we’re in this together. It’s a gesture that belongs as much to the bedroom as it does to the ballfield, a spark of intimacy that can ignite a moment or a movement. Burke understood that. He lived it. And in doing so, he gave us a way to celebrate that’s as bold and unapologetic as he was.

A Call to Celebrate

So, the next time you high-five someone—whether it’s over a home run, a killer drag performance, or a late-night confession—think of Glenn Burke. Think of the man who ran onto that field, his arm raised high, his heart wide open. Think of the Castro in the 1970s, alive with the sound of disco and the promise of liberation. Think of the courage it took to be out, to be proud, to be sexy in a world that wanted him to be anything but.

(Burke’s high five is a reminder that queer people have always been culture-makers, shaping the world with our joy, our pain, and our unyielding fabulousness. It’s a call to keep pushing, to keep loving, to keep slapping hands in defiance of anyone who tells us we don’t belong. As Lady Gaga once sang, “I’m beautiful in my way, ‘cause God makes no mistakes.” Glenn Burke lived that truth, and his legacy is a high five to every queer person still fighting to be seen.

(

0 Comments