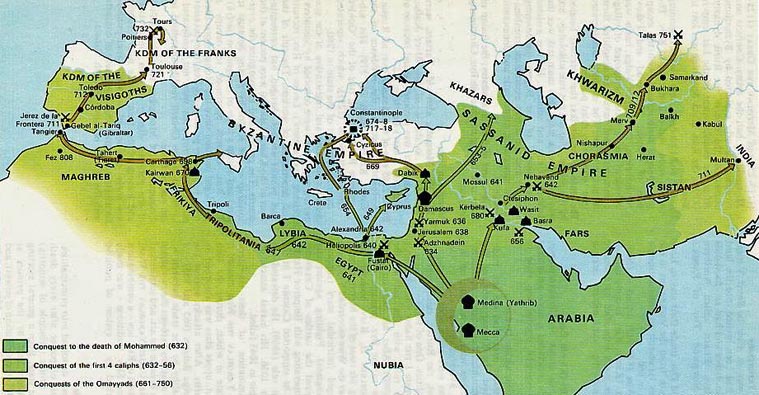

The rapid and expansive Arab Conquest during the 7th and 8th Centuries CE established an empire spanning three continents, extending from the Indus River to the Atlantic. Its profound impact continues to resonate today. While scholars debate the precise reasons behind its success, many attribute it to the combination of state formation in Arabia, ideological unity, and effective mobilization. This conquest unfolded gradually, in a series of interconnected phases across a vast geographical expanse. By its conclusion, the established order had been definitively supplanted, giving rise to a new global power.Before the Arab Conquest

Cras eget sem nec dui volutpat ultrices.

Cras eget sem nec dui volutpat ultrices.

The decline of Persia from 633 to 651 CE

The Arab Conquest commenced with incursions into southern Mesopotamia, followed by the conquest of various towns and settlements. This incited a response from Sassanian King Yazgerd III (r. 632-651), who mobilized an army to confront the Arab invaders. The pivotal Battle of al-Qadisiyyah in 636 CE, spanning several days, resulted in the complete annihilation of the Sassanian forces. With this triumph, the Arabs gained control over all of Mesopotamia, including the Sassanian capital, Ctesiphon. Despite subsequent attempts by the Sassanians to reclaim their lost territories, their efforts proved futile. By 642 CE, the Arab forces had crossed the Zagros Mountains into the Iranian plateau and secured another significant victory at the Battle of Nahavand. This decisive Arab triumph at Nahavand spelled the demise of the Sassanian Empire, compelling Yazgerd III to flee towards the eastern regions.

Cras eget sem nec dui volutpat ultrices.

Cras eget sem nec dui volutpat ultrices.

Following the victory at Nahavand, the Arab forces advanced gradually into Persia along three strategic axes. Despite the destruction of the Sassanian army, the Arabs still encountered formidable Persian principalities and city-states, which they systematically subdued one by one. A significant challenge arose in 644 CE when a major rebellion threatened to reverse the Arab conquest in Persia. Although the assassination of Yazgerd III by a local satrap in 651 CE marked the end of this phase of the conquest, Persian resistance persisted. Guerrilla warfare and uprisings persisted for decades before the Caliphate fully established control over the region.

The Levant from 634 to 641 CE

Cras eget sem nec dui volutpat ultrices.

Cras eget sem nec dui volutpat ultrices.

The Arab Conquest of the Levant gained momentum in 634 CE following initial raiding activities. In response to the Byzantine buildup of armies to repel the invaders, command of the Arab forces was entrusted to Khalid ibn al-Walid, renowned as one of the greatest commanders of the Arab Conquest. Khalid led his forces on a rapid desert march to surprise the Byzantines from the rear. In 636 CE, Khalid and his troops confronted a Byzantine army led by Emperor Heraclius (r. 610-641 CE), who had previously defeated the Sassanians in a war. At the Battle of Yarmouk, a misunderstood command threw the Byzantine forces into disarray, enabling the Arabs to achieve a decisive victory. In the aftermath of this defeat, Heraclius ordered Byzantine forces to withdraw from Syria and establish a more fortified position in Anatolia.

Cras eget sem nec dui volutpat ultrices.

Cras eget sem nec dui volutpat ultrices.

Despite the evacuation of Byzantine forces, the surrender of towns and cities in the Levant did not occur immediately. Several locales fiercely resisted the Arab conquest. Damascus fell to the Arabs for the second time in 636 CE, alongside Baalbeck, Homs, and Hama. Jerusalem endured a two-year siege before its garrison capitulated due to starvation. Caesarea Maritima, being resupplied by sea due to the Arab navy's absence, held out until 640 CE when it was stormed and conquered. By 641 CE, the last remaining cities in the region had been subdued, although skirmishes persisted thereafter. The Byzantines pursued a strategy of aiding guerrilla fighters in the hills and mountains while launching naval raids. Control of the mountainous Anatolian region oscillated between the Arabs and Byzantines until the arrival of the Turks in the 11th century.

The period of 639 to 642 CE in Egypt

Cras eget sem nec dui volutpat ultrices.

Cras eget sem nec dui volutpat ultrices.

The Arab conquest of Egypt stands out as the swiftest and most comprehensive among their conquests. This region, recognized for its wealth and strategic significance, held considerable familiarity for the Arabs. Egypt not only served as the Byzantine Empire's breadbasket but also constituted a major source of tax revenue and served as a gateway into Africa. 'Amr ibn al-'As (c. 573-664 CE) spearheaded the Arab forces, initiating the invasion independently in 639 CE. The Byzantine forces stationed in the province mainly comprised militia, originally intended for a policing role. After traversing the Sinai, the Arabs seized the fortress city of Pelusium, a longstanding guardian of Egypt's entrance. Despite a Byzantine counterattack, the Arabs proceeded towards the critical stronghold of Babylon, situated near modern Cairo. Arab triumphs at the battles of Heliopolis in 640 CE and Babylon in 641 effectively partitioned Egypt into two regions.

Following the demise of Byzantine Emperor Heraclius in 641 CE, the Byzantine defenders of Egypt lost hope of receiving reinforcements. Meanwhile, the Arabs turned northward and entered the Egyptian delta. Here, their progress was hindered by the river and a scarcity of boats. Alexandria, the last major city to succumb to the Arabs, surrendered in 642 CE. Although the Byzantines briefly regained control of Alexandria in 644 CE through an amphibious assault, they were eventually expelled. The conquest of Egypt severely depleted the resources of the Byzantine Empire and secured the future prosperity of the Caliphate. Therefore, this phase of the Arab conquest could be considered the most consequential.

The conquest of the Maghreb spanning from 647 to 709 CE

Cras eget sem nec dui volutpat ultrices.

Cras eget sem nec dui volutpat ultrices.

The Arab conquest of the Maghreb, or North Africa, unfolded over the course of nearly a century and progressed in distinct stages. The region was divided between two factions: the Byzantines controlled the major coastal cities and their surroundings, while the Berbers held sway over the interior. The initial incursions targeted Byzantine Cyrenaica and Tripolitania (modern Libya), commencing in 647 CE after a period of raiding.

Local Byzantine governor Count Gregory, having declared independence, sought to repel the Arab invasion but fell in battle. His successor negotiated an Arab withdrawal in exchange for tribute. However, the full-scale invasion did not resume until 665 CE under the auspices of the new Umayyad Caliphate (661-750 CE). Led by Uqba ibn Nafi (d. 683 CE), this force established Kairouan, near modern Tunis, as the capital of the Islamic province of Ifriqiya and reached the Atlantic Ocean.

Subsequently, Berber and Byzantine uprisings erupted, resulting in the ambush and demise of Uqba and his army. The second invasion stalled outside Carthage in 689 CE when Byzantine reinforcements decimated another Arab force in 688 CE. The third and final invasion commenced after the Arabs captured Carthage in 695 CE. Although another formidable Byzantine contingent was dispatched to reclaim Carthage and managed to hold the city until 698 CE, the Arabs ultimately razed the city to deter Byzantine reprisals.

Following this, a Berber rebellion, led by Queen Kahina, expelled the Arabs from the Maghreb. The rebellion was met with harsh retaliation; Kahina fell in battle in 703 CE, and by 709 CE, Arab authority was reinstated across the Maghreb. Only the minor Byzantine enclave of Ceuta, commanded by Count Julian, remained by this point. Tensions between the Arabs and Berbers persisted, erupting into open revolt as the Arabs imposed heavy taxes and viewed the Berbers as inferior.The Arab conquest of Transoxiana, spanning from 673 to 751 CE,

Cras eget sem nec dui volutpat ultrices.

Cras eget sem nec dui volutpat ultrices.

The Arab conquest of Persia extended into Transoxiana, the modern Central Asian region that was nominally under the Sassanian Empire's jurisdiction. Here, the Arab forces encountered staunch resistance from local populations, remnants of the Sassanian regime, and Turkic tribes backed by the Tang Dynasty of China (618-907 CE). The Chinese considered this area within their sphere of influence and sought to safeguard the crucial trade routes of the Silk Road. Arab incursions intensified in 673 CE, targeting the principalities of Bukhara and Samarkand in Sogdiana. These cities witnessed multiple conquests and reconquests over the years. The bulk of the region fell under Arab control between 705 and 715 CE under the leadership of Qutayba ibn Muslim al-Bahili (669-716 CE). However, in 719 CE, local princes appealed to their nominal Turkic overlords, the Turgesh, for assistance. With Turgesh military backing, the Sogdians staged a revolt.

The Sogdian uprising persisted until 738 CE, resulting in significant loss of life and resources. A crucial factor in the Arab victory was the assassination of the Turgesh khan, leading to internal strife within their ranks. The revolt resulted in the destruction of much of the Sogdian culture and heritage, with tens of thousands deported to the Middle East. Concurrently, Arab advances into the Fergana Valley provoked a robust response from the Tang Chinese, who had also formed an alliance with the formidable Tibetan Empire, posing a threat to Tang control of the Tarim Basin and its lucrative cities and trade routes. The Arab and Tang forces clashed at the Battle of Talas in 751 CE. The ensuing Arab triumph solidified their dominance over Transoxiana, although the spread of Islam in the region would require many more years.The conquest of Sindh, occurring between 711 and 714 CE,

Cras eget sem nec dui volutpat ultrices.

Cras eget sem nec dui volutpat ultrices.

The first major invasion of Sindh, encompassing modern-day Pakistan and India, during the Arab Conquest, was spearheaded by Muhammad bin Qasim. Leading his forces along the coastline from Makran in Persia to the Indus Valley, Muhammad bin Qasim encountered a region where most towns and cities submitted to the Arabs through peace agreements. In exchange for their compliance, local elites were permitted to retain their positions of authority. The Brahmin Dynasty of Sindh (632-724 CE), also known as the Chacha dynasty, ruled this area. Upon the Arab conquest of Brahmanabad on the Indus, Muhammad bin Qasim reaffirmed the rights and privileges of the Brahmin elite, facilitating the region's submission to Arab rule. However, the Brahmans continued their persecution of the Jats, an ethnic minority comprising pastoralists and farmers.

The Eastern Jats aligned themselves with Dahir, a ruler of Sindh, in an attempt to resist the Arab conquest. This led to significant conflict, ultimately culminating in victory for the Arabs under Muhammad bin Qasim. Having secured control over the lower Indus Valley, an expedition comprising approximately 10,000 cavalrymen was dispatched upriver to obtain the submission of local rulers. Meanwhile, Muhammad bin Qasim led the remainder of his army to the Kashmir frontier to subjugate the remaining territories. In 715 CE, Muhammad bin Qasim was recalled by the Caliph but died en route. Subsequent Arab advances were hindered by the Gurjara (6th-12th Century CE) and Chalukya (543-753 CE) kingdoms, as well as the Rashtrakuta Empire (753-982 CE). As a result, Caliphs favored a policy of religious conversion over outright conquest.The period spanning from 711 to 721 CE in Hispania and Septimania

Cras eget sem nec dui volutpat ultrices.

Cras eget sem nec dui volutpat ultrices.

Cras eget sem nec dui volutpat ultrices.

Cras eget sem nec dui volutpat ultrices.

By 716 CE, the Visigothic realm had been confined to the province of Septimania, roughly corresponding to the present-day region of Languedoc-Roussillon in modern France. Raids into Septimania commenced in 717 CE and persisted over the following years as the territory gradually fell under Arab control. In 719 CE, Al-Samh ibn Malik al-Khawlani (d. 721), the newly appointed Arab governor, successfully conquered Narbonne, the provincial capital. During the same year, he established permanent garrisons and integrated the territory into Al-Andalus, the former Visigothic domain. The following year, in 721 CE, Al-Samh met his demise during the Battle of Toulouse, at the hands of Odo of Aquitaine (r. 700-735 CE). This temporarily halted further Arab invasions into the region, although the Visigothic nobility had effectively capitulated and agreed to live under Umayyad rule.

Legacy of the Arab Conquest

Cras eget sem nec dui volutpat ultrices.

Cras eget sem nec dui volutpat ultrices.

The era known as the Arab Conquest is generally regarded as having drawn to a close around 751 CE with the overthrow of the Umayyad Caliphate by the Abbasid Caliphate (750-1517 CE). By this juncture, the population of non-Arab converts had significantly increased, enhancing their power and influence within the Islamic world. While non-Arab Muslims had played crucial roles during the Arab Conquest, it had predominantly been the Arabs who had taken center stage. In the ensuing years, the Arabs continued to expand their territories across the Caliphate, remaining a formidable military force for many generations. However, they did not replicate the rapid and extensive territorial gains witnessed during the period of the Arab Conquest.

The Arab Conquest of the 7th and 8th Centuries CE stands as one of the most consequential events in world history. It facilitated the rapid expansion of Islam beyond the Arabian Peninsula, transforming it into a globally influential religion and shaping an Arabized and Islamized Middle East. The once formidable Byzantine and Sassanid Empires were swiftly supplanted by this emergent power, ushering in an era where one could traverse from the eastern frontiers of Tang China to the shores of the Atlantic Ocean without encountering the borders of any other kingdom. Over time, this new empire not only precipitated significant religious and political transformations but also heralded new cultural, economic, and scientific developments that profoundly impacted the world.

0 Comments