While inspirational messages often emphasize that money can't buy happiness, a deeper look reveals a more complex relationship. Wealthy countries consistently rank higher in happiness reports, and psychological research confirms a strong correlation between personal wealth and life satisfaction. This correlation even extends to the super-rich, suggesting that the more money one has, the happier they tend to be.

However, does this mean that the path to true happiness lies solely in financial wealth? Are the inspirational messages simply wrong, or is there more to happiness than just money? Perhaps happiness is a multi-faceted concept, influenced by a variety of factors, including financial security, but also relationships, health, personal growth, and a sense of purpose. Understanding this complexity is crucial in navigating the pursuit of happiness in a world that often equates wealth with well-being.

The constant question of whether increasing wealth is essential for human well-being intrigues me both personally and professionally. As a researcher exploring the relationship between human actions and environmental sustainability, I wonder if the relentless pursuit of economic growth is truly necessary for us to flourish. Industrialized societies have long prioritized economic expansion, often accepting severe environmental damage, like climate change, rather than risking economic stability. Consequently, our industrialized way of life now jeopardizes the very existence of all complex life on Earth. Is this self-destructive path driven by the belief that our happiness hinges on accumulating more wealth?

To investigate this further, I collaborated with anthropologist Viki Reyes-García from the Autonomous University of Barcelona. Since most studies on happiness focus on Western societies, which don't represent the full range of human experiences, we aimed to examine the happiness levels of people who are less reliant on money.

Reyes-García spearheaded a global research initiative to investigate the well-being of small-scale societies in the face of climate change. Assembling a team of researchers, she embarked on a mission to survey a diverse range of communities across five continents, with a particular focus on those who identify as Indigenous and rely primarily on their local ecosystems for sustenance. These groups, often characterized by minimal interaction with monetary economies, offered a unique perspective on well-being that could shed light on the impacts of climate change on marginalized populations. The survey aimed to assess overall life satisfaction among nearly 3,000 participants, utilizing a standardized question that would enable direct comparison with individuals in industrialized societies. This approach would provide valuable insights into the relative well-being of different groups and inform efforts to address the challenges faced by those most vulnerable to climate change.

Reaching the isolated communities in South American jungles, African grasslands, and the mountains of South Asia was challenging. We conducted hour-long interviews with randomly selected residents in over 100 villages, using surveys translated into local languages. Since most lacked regular incomes, we estimated average earnings from the value of purchased household possessions, often equating to a few dollars per person daily.

The survey revealed surprising results: despite having very limited resources, people in these communities reported being as happy as individuals in wealthier nations. While satisfaction levels varied, some communities reported remarkably high happiness scores, even exceeding national averages in many affluent countries. Our key finding is that even with minimal incomes, a significant portion of these individuals consider themselves very happy.

The observation that individuals in some small-scale societies report higher levels of satisfaction than those in wealthier countries, despite numerous studies linking higher income with greater happiness, raises an important question. How can this be reconciled?

Our research suggests that placing excessive emphasis on the correlation between money and happiness may be misleading. While wealth is easily quantifiable and thus frequently studied, other factors play a significant role in life satisfaction. Notably, our findings revealed a significant correlation between imputed wealth and satisfaction in small-scale societies, but its impact was minor compared to other societal characteristics. Furthermore, the Easterlin paradox demonstrates that increased wealth within a society doesn't always translate to increased life satisfaction for everyone.

This implies that focusing solely on monetary wealth as a determinant of happiness oversimplifies a complex issue. A broader perspective, incorporating various social, cultural, and environmental factors, is essential for a comprehensive understanding of life satisfaction.

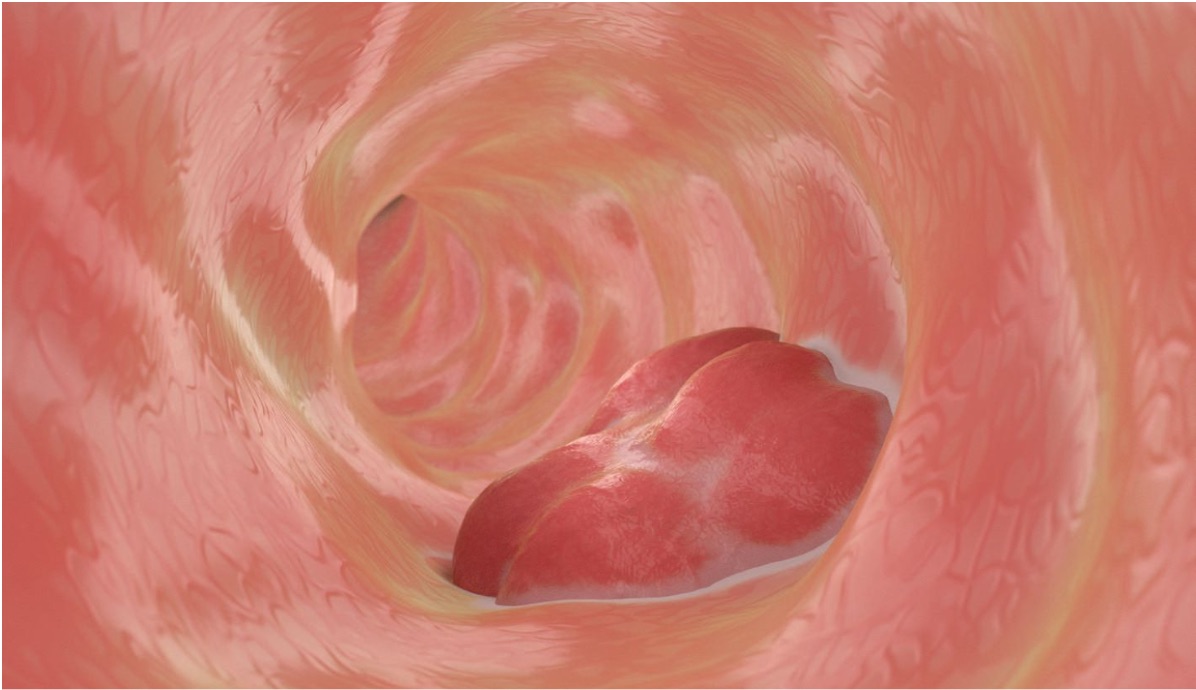

Material wealth is not the sole determinant of happiness, as research highlights the crucial role of social relationships. Humans, inherently social creatures, crave a sense of belonging and support from their community, which is fostered through strong interpersonal bonds and a perceived social standing. However, wealth does not necessarily translate into strong social connections. The studied communities, while financially limited, are not deprived of essential needs and often enjoy a lifestyle immersed in nature, a factor frequently associated with greater well-being. This connection with the natural world, alongside a strong social fabric, may contribute to a fulfilling life even in the absence of material abundance. Thus, the pursuit of happiness extends beyond financial gain, encompassing social bonds and environmental connection.

Additionally, the World Happiness Report's reliance on the "Cantril ladder" survey question might skew its findings towards wealthier nations. Research indicates that this method, where individuals visualize a ladder with their ideal life at the top, tends to emphasize relative income rather than overall life satisfaction. This contrasts with our study and others, which directly asked participants to quantify their life satisfaction. Consequently, the World Happiness Report might reveal more about contentment with income levels than overall well-being. Moreover, it's important to acknowledge the potential impact of social comparison on happiness, particularly in societies with high levels of income inequality. While not directly measured in our study, it's worth noting that the communities we examined generally exhibit less income inequality than many affluent industrialized countries. This suggests that factors beyond income, such as social cohesion and support networks, may also play a significant role in shaping overall life satisfaction.

The research reveals a compelling insight for those residing in industrialized nations: our relentless pursuit of wealth may not be the sole path to happiness. While financial resources are undeniably crucial for fulfilling basic necessities, the study suggests that the level of material wealth currently sought after in industrialized societies significantly surpasses what is truly needed for a satisfying existence. This finding carries positive implications for our planet, as it indicates that achieving a balance between meeting everyone's basic needs and mitigating climate change is a feasible goal.

In the context of our monetized societies, money undoubtedly plays a vital role, and having more of it can often enhance our lives. However, the study emphasizes that genuine happiness and fulfillment are not solely determined by accumulating excessive material possessions. Instead, it underscores the importance of recognizing that a fulfilling life can be achieved with far less material wealth than we currently strive for. This shift in perspective could potentially pave the way for a more sustainable and equitable future, where the focus shifts from endless consumption to prioritizing well-being and environmental preservation.

Our research with Reyes-García and colleagues indicates that many societies can learn from the strengths of small-scale communities to address their own shortcomings. The Western emphasis on individualism, the pursuit of material wealth, and the growing isolation in the digital age may all hinder happiness. At this juncture, the most effective way to enhance well-being in affluent nations might be to prioritize shared human connection over economic growth. This shift could also be crucial for safeguarding the future of life on our planet.

0 Comments