In my research on early European farmers, I have been intrigued by a recurring pattern: communities often formed dense villages, later dispersed for centuries, and then re-established urban centers, only to abandon them once more. What accounts for this behavior?

Archaeologists frequently attribute urban collapse to factors like climate change, overpopulation, and social pressures. However, a new hypothesis suggests that disease played a crucial role. Close interactions with animals likely introduced zoonotic diseases, leading to the abandonment of densely populated settlements until new strategies for spatial organization emerged that offered greater resilience to disease. My colleagues and I explored how the layouts of later settlements could have affected disease transmission.

The First Cities: Crowded and VulnerableÇatalhöyük, in modern Turkey, is the oldest known farming village, dating back over 9,000 years. Thousands lived in tightly packed mud-brick homes, accessed via ladders through roof trapdoors, and even buried select ancestors beneath their floors. Despite the ample space of the Anatolian Plateau, residents clustered closely together.

For centuries, the people of Çatalhöyük herded sheep and cattle, farmed barley, and crafted cheese. Their vibrant culture is reflected in murals depicting bulls and dancing figures. They maintained cleanliness in their organized homes, often replastering their walls multiple times a year. Yet, this thriving community mysteriously declined by 6000 BCE, dispersing into smaller settlements across the floodplain. Other large farming groups also scattered, leading to increased nomadic livestock herding and distinct, separate homes instead of the close-knit structures of Çatalhöyük.

Did Disease Influence This Abandonment?At Çatalhöyük, archaeological findings reveal a mingling of human and cattle remains in burials and refuse, indicating that the close quarters likely facilitated the spread of zoonotic diseases. Ancient DNA evidence shows the presence of tuberculosis from cattle as early as 8500 BCE and salmonella by 4500 BCE. Given that the contagiousness of Neolithic diseases likely intensified over time, densely populated areas such as Çatalhöyük may have reached a threshold where the risks of disease outweighed the advantages of communal living.

A Different Approach 2,000 Years LaterBy 4000 BCE, large urban populations re-emerged in the mega-settlements of the ancient Trypillia culture, located west of the Black Sea. Thousands inhabited settlements like Nebelivka and Maidanetske in present-day Ukraine.

If disease prompted earlier dispersal, how did these mega-settlements thrive? Unlike the crowded homes of Çatalhöyük, the Trypillia settlements featured hundreds of two-story wooden houses arranged in spaced concentric ovals, grouped into pie-shaped neighborhoods, each containing a large assembly house. The diverse pottery found in these assembly houses indicates that families gathered to share food.

This design implies a potential strategy: the clustered, lower-density layout of Nebelivka could have effectively reduced the risk of widespread disease outbreaks.

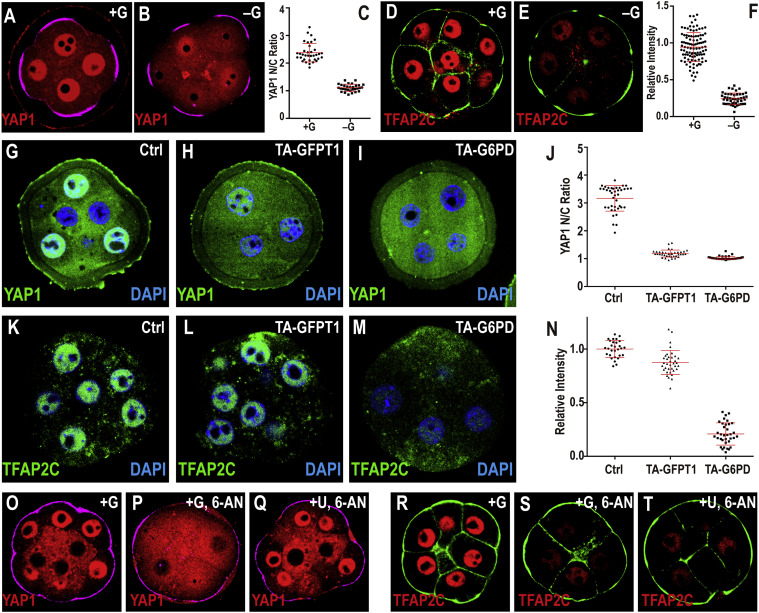

Testing the HypothesisTo investigate this, archaeologist Simon Carrignon and I adapted computer models from previous studies on how social distancing influences pandemic spread. We collaborated with cultural evolution scholar Mike O’Brien and Nebelivka archaeologists John Chapman, Bisserka Gaydarska, and Brian Buchanan to analyze how the Trypillia settlement layout might disrupt disease transmission.

Our simulations relied on a few assumptions: early diseases were likely transmitted through food, and people frequented neighbors more than distant households. We ran millions of simulations to see if this neighborhood clustering could sufficiently curb disease outbreaks. When interactions with other neighborhoods were infrequent—about 5% to 10% of the time compared to within their own neighborhood—the Nebelivka layout showed a significant reduction in early foodborne disease outbreaks. This finding suggests that the clustered layout allowed early farmers to coexist in low-density urban settings amid rising zoonotic diseases.

Instincts and InnovationsThe residents of Nebelivka may not have intentionally designed their neighborhoods for disease prevention, but human nature tends to steer people away from signs of contagion. Similar to Çatalhöyük, the inhabitants maintained cleanliness in their homes, and many houses in Nebelivka were purposefully burned at various times, likely as a method of pest control.

As time progressed, some early diseases evolved to spread through means other than food. For example, tuberculosis eventually became airborne, and the plague bacterium, Yersinia pestis, adapted to fleas, spreading via rats that ignored neighborhood boundaries.

Did these new disease vectors spell doom for ancient cities? The Trypillia mega-settlements were abandoned by 3000 BCE, similar to Çatalhöyük centuries earlier, as populations dispersed into smaller groups. Some geneticists theorize that the emergence of plague in the region around 5,000 years ago contributed to this abandonment.

The first cities in Mesopotamia emerged around 3500 BCE, followed by others in Egypt, the Indus Valley, and China. These urban centers, home to tens of thousands, featured specialized craftspeople organized in distinct neighborhoods.

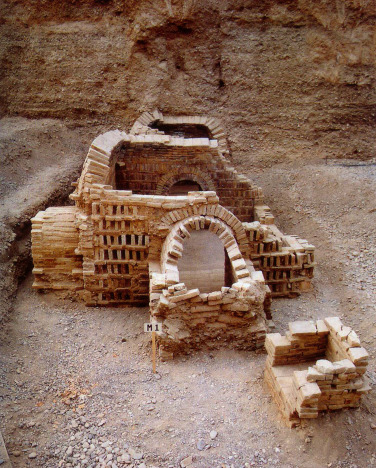

In this phase, city dwellers were not cohabiting closely with livestock. Instead, cities became trade hubs where food was imported and stored in large granaries, such as the one in Hattusa, capable of feeding 20,000 for a year. Public sanitation improved with water systems like the canals in Uruk and public baths in Mohenjo Daro.

These early cities across the globe laid the groundwork for civilization, arguably shaped by millennia of diseases and humanity's adaptive responses, tracing back to the earliest farming villages.

R. Alexander Bentley is a professor of anthropology at the University of Tennessee.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article

0 Comments