In 1977, the Arpanet was still a relatively exclusive network, primarily used by universities and research centers involved in cutting-edge projects funded by the Department of Defense. This was a time when the concept of a global, interconnected network of computers was still in its infancy. The average person wouldn't have even heard of the Arpanet, let alone used it. For those universities lucky enough to be connected, it was a powerful tool for collaboration and information sharing, a glimpse into the future of communication. Imagine a world where accessing this "network of networks" could give a university a significant advantage in attracting top students! This was a time when personal computers were just starting to emerge. The Apple I, a barebones machine compared to today's standards, had just been released, marking a significant step towards making computers more accessible. However, the IBM PC, which would later become a household name, was still four years away from its launch in 1981. This puts into perspective how early it was in the personal computing revolution and how limited access to technology was for most people. The world was on the cusp of a digital revolution, but it was still very much in its early stages.

In the early days of the internet, access was largely confined to universities, research institutions, and government agencies. This was primarily due to the technological limitations of the time. The internet's precursor, ARPANET, was developed in the late 1960s as a military-funded project, and its initial purpose was to connect research institutions for collaborative purposes. Personal computers were not yet commonplace, and the internet relied on dial-up modems with painfully slow speeds. Imagine waiting several minutes for a single image to load! This limited accessibility significantly restricted the potential for widespread use of online communication tools like email or chat rooms, which were in their infancy then. Furthermore, the complexity of early operating systems and the lack of graphical user interfaces made the internet intimidating and inaccessible to the average person. The high cost of computers and internet access further exacerbated this digital divide, creating a significant barrier to entry for most people. This period, often referred to as the "pre-web era," saw limited growth in internet usage and hindered its development into the ubiquitous platform we know today. It wasn't until the development of the World Wide Web in the early 1990s, with its user-friendly graphical interface and hyperlinks, that the internet truly began to take off and become a mainstream phenomenon.

While universities and corporations were focused on their own research, neglecting the development of internet technologies for the general public in the mid-1970s, Ward Christensen pioneered a grassroots movement in Chicago that would lay the foundation for online social interaction. This was a time when computers were largely seen as expensive, complex machines used by governments and large institutions, not something individuals could own or use to connect with each other. Christensen, a member of the Chicago Area Computer Hobbyists' Exchange (CACHE), recognized the potential for computers to facilitate communication and community. He created and freely shared a program called MODEM, enabling computers to communicate over telephone lines. This was achieved through "acoustic coupling," a technique where the computer's digital signals were converted into audible tones that could be transmitted through the telephone handset. Essentially, one computer would "talk" to another by playing sounds into the phone, and the receiving computer would "listen" and decode those sounds back into digital data. This innovative process, born out of the desire to connect and share information, gave rise to the term "modem" (short for MOdulator-DEModulator), coined by Christensen's collaborator Randy Suess. The term "modem" has since become ubiquitous, now referring to any device facilitating computer-to-computer communication over telephone lines, whether through dial-up, DSL, or cable connections. Christensen's work, fueled by the spirit of the early hacker culture that valued open access and collaboration, laid the groundwork for the bulletin board systems (BBSs) that would flourish in the years to come, and ultimately paved the way for the internet as we know it today.

To truly grasp the significance of Christensen's pursuit of building a personal computer in the early 1970s, it's crucial to understand the technological landscape of the time. Mainframe computers, behemoths that occupied entire rooms and cost a fortune, reigned supreme. These were the tools of large corporations, universities, and government agencies, not something an individual engineer, even one working for IBM, could realistically own. The very idea of a "personal computer" was still in its infancy.

The early 1970s were a pivotal time in the history of computing. The invention of the microprocessor, a single chip containing all the essential functions of a computer's central processing unit, was revolutionary. Intel's 8008, encountered by Christensen at the seminar, was a pioneering example, albeit a primitive one by today's standards. It marked a significant step towards miniaturizing computers and making them accessible to a wider audience.

Christensen's eagerness to build a computer using the 8008 reflects the excitement and sense of possibility surrounding this nascent technology. His determination to learn TTL (Transistor-to-Transistor Logic), a key technology for building digital circuits at the time, highlights the DIY spirit that characterized early computer enthusiasts. These were individuals driven by a passion to explore the frontiers of computing, often with limited resources and relying on their ingenuity. Salvaging components from discarded circuits was a common practice, demonstrating a resourcefulness born out of necessity.

Christensen's journey to build a personal computer in the early 1970s exemplifies the pioneering spirit that drove the personal computer revolution. It was a time of experimentation and discovery, where individuals pushed the boundaries of technology, paving the way for the ubiquitous computing devices we take for granted today.

To put his newfound knowledge of Intel microprocessors to the test, Christensen acquired an Altair personal computer, finally realizing his dream of owning a computer. This was no ordinary feat in the mid-1970s. The Altair 8800, released in 1975, was a groundbreaking machine. Considered the spark that ignited the personal computer revolution, it was featured on the cover of Popular Electronics magazine and became a symbol of the burgeoning home computing movement. It was sold as a kit, requiring users to assemble it themselves, a testament to the technical expertise and dedication of early computer enthusiasts.

While experimenting with the Altair, Christensen joined the CACHE (Chicago Area Computer Hobbyist's Exchange), a group of like-minded individuals who were pushing the boundaries of what these early computers could do. CACHE, like other hobbyist groups springing up across the country at the time, served as a crucial hub for sharing knowledge, software, and ideas. It was a pre-internet era where communities like CACHE fostered innovation and collaboration, much like online forums and open-source communities do today. It was within this community that the first version of Modem was shared, and where Christensen met Randy Suess, a fellow CACHE member who would collaborate with him to develop the first Bulletin Board System (BBS) in January 1978. This was a pivotal moment in the history of electronic communication. Before the internet and widespread email adoption, BBSs provided a platform for users to connect with each other, share files, and engage in online discussions, laying the groundwork for the online communities we know today. Christensen and Suess's creation, known as CBBS (Computerized Bulletin Board System), became a blueprint for thousands of BBSs that would follow, forever changing the way people interacted and communicated.

In 1977, amidst the burgeoning personal computer revolution, Ward Christensen embarked on a project that would fundamentally change how computers communicate. Working with the then-dominant CP/M operating system, a precursor to MS-DOS, he sought a way to overcome the limitations of transferring data between computers. Floppy disks were fragile and couldn't be easily mailed, while the internet as we know it didn't exist. Christensen's ingenious solution was to leverage the ubiquitous audio cassette recorder. By converting the digital 1s and 0s of computer data into audible tones, he could store the information on a cassette tape, physically transport it, and then have another computer "listen" to the tape and reconstruct the data. This was the birth of the "Modem program," a name derived from "modulator-demodulator," reflecting the process of converting digital signals to analog audio and back again. This breakthrough, building upon earlier acoustic coupler technology used in telegraphy, paved the way for the dial-up modems that would connect millions to bulletin board systems (BBSs) and the nascent internet in the years to come. Christensen's innovation, born from the constraints of the era, ultimately democratized access to information and laid the foundation for the interconnected digital world we inhabit today.

In the early days of personal computing, when modems were first becoming popular, transferring files between computers was a significant challenge. Imagine a time before the internet as we know it, when connecting with another computer often meant dialing directly into it using a phone line. This was a slow and error-prone process, with noise on the phone line often corrupting data. In this environment, a program called "Modem," developed within a group of early computer enthusiasts known as the "Cache group," emerged as a crucial tool. This program, shared freely among users, provided a basic framework for transferring files, laying the foundation for what would become a revolution in digital communication.

Ward Christensen, recognizing the limitations of the original Modem program, collaborated with Keith Peterson to create XMODEM. This new protocol introduced important features like checksums, which helped ensure the integrity of the data being transmitted by verifying that the received data matched the sent data. XMODEM quickly became the gold standard, spreading rapidly across different computer platforms, from the early Apple II and Commodore 64 to the rising IBM PC and the powerful Unix systems. This was a time of intense creativity and collaboration in the computing world, with programmers freely sharing and modifying code to improve it. XMODEM, with its open design, became a fertile ground for experimentation.

Programmers, driven by a desire for faster and more reliable file transfers, began "hacking" XMODEM, adding features like sliding windows (which allowed for sending multiple data packets at once) and improved error correction. This culture of collaborative tinkering mirrored the early days of the internet itself, where open protocols and shared knowledge fueled innovation. Chuck Forsberg, a prominent figure in this movement, developed a highly efficient version of XMODEM in the C programming language for Unix systems, paving the way for his groundbreaking ZMODEM protocol. ZMODEM, with its sophisticated error-checking and ability to resume interrupted transfers, represented a significant leap forward, further solidifying the legacy of "Modem" and XMODEM in shaping how we communicate and share information in the digital age.

Enabling computers to communicate was just the initial step in establishing a true computer network. In the early days, this involved physically linking computers with cables, a far cry from today's wireless world. Initially, these digital connections were primarily a convenient way for hobbyists to exchange software without the need for physical exchange of floppy disks or magnetic tapes, which were the primary storage media at the time. Imagine the inconvenience of having to mail a floppy disk to someone just to share a simple program! This desire for easier sharing led to the emergence of "communication programs," rudimentary software that allowed computers to interact with each other. This, in turn, spurred the development of distributed systems, forming specialized networks for message exchange, information sharing, and bulletin boards. These early networks, often running on now-obsolete protocols like X.25, were the precursors to the internet as we know it. They fostered the growth of early online communities, providing a virtual space for people to connect and share ideas. These networks also served as a breeding ground for the digital underground cultures of the 1980s, with Bulletin Board Systems (BBSs) as their fundamental building blocks. BBSs were essentially online forums where users could dial in with their modems and engage in discussions, download files, and even play games. This was a time of experimentation and exploration in the digital realm, with pioneers pushing the boundaries of what was possible with these new communication tools, laying the foundation for the interconnected world we live in today.

To truly grasp the significance of Ward Christensen and Randy Suess's creation of CBBS in 1978, we need to step back and consider the technological landscape of the time. The internet as we know it simply didn't exist. ARPANET, the precursor to the internet, was limited to academic and government institutions. For the average person, the idea of connecting to another computer, let alone having a conversation or sharing files, was a futuristic concept.

Modems, those clunky devices that translated computer data into audible signals for transmission over telephone lines, were a relatively new technology. They were slow, often topping out at 300 bits per second (imagine downloading a single image today at that speed!), and expensive.

Yet, amidst this nascent digital era, the desire to connect and communicate was strong. Hobbyists, tinkerers, and early adopters of personal computers like the Altair 8800 yearned for a way to share information and ideas. Enter CBBS, the first public dial-up Bulletin Board System. Imagine a world without email, social media, or instant messaging. CBBS was a revelation. Suddenly, like-minded individuals could connect with each other remotely, engage in discussions, and exchange files. It was a virtual community hub, a precursor to the online forums and social networks that would follow decades later.

CBBS, and the countless other BBSs that sprung up in its wake, fostered a vibrant online culture. They were hubs for everything from technical discussions and software sharing to gaming and social interaction. This was the primordial soup of online community building, where the norms of online etiquette and communication were first established. It was a time of experimentation and excitement, where the boundaries of what was possible in the digital realm were constantly being pushed.

So, while a BBS might seem like a quaint relic today, it's crucial to remember that it was a pivotal step in the evolution of online communication. It laid the groundwork for the interconnected world we live in today, where connecting with someone on the other side of the globe is just a click away.

The BBS Network: A Digital Pony Express

In the early days of personal computing, before the internet as we know it existed, people found ingenious ways to connect and share information. One such innovation was the Bulletin Board System (BBS) network, a precursor to the modern internet. Imagine a world without the World Wide Web, where computers were not always online, and accessing information meant dialing into a local BBS using a modem. These BBSs were often run by individuals from their homes or businesses, creating a vibrant community of users who could exchange messages, files, and even play games.

Information within the BBS network was shared across all nodes, allowing messages from Los Angeles or New York to be accessible from the San Francisco node. This was achieved through a system similar to the Pony Express, where messages would be passed from one node to another, eventually reaching their destination. BBS services were typically free, except for the cost of phone calls needed for message retrieval and posting. Connections between nodes were not constant but occurred at specific times, often during off-peak hours when phone rates were lower to minimize costs.

This process, known as "Store and Forward," involved receiving and storing messages at a node, and then forwarding them to other nodes during the night through automated calls managed by the computers. This method of information transfer was a clever workaround for the limited technology of the time, allowing users to connect and share information across vast distances. The BBS network played a crucial role in the development of online communities and paved the way for the internet revolution that followed.

To truly grasp the significance of Rheingold's words, we need to step back in time to the era before widespread internet access. Imagine a world where information flowed primarily through controlled channels like television, radio, and print media. In this landscape, Bulletin Board Systems (BBSs) emerged as revolutionary spaces for communication and community building. These were essentially computer systems run by individuals, often from their own homes, allowing users to connect via dial-up modems. Think of them as localized, pre-internet versions of online forums or social media platforms.

The sysops, who were often hobbyists and technology enthusiasts, played a crucial role in this ecosystem. They not only shouldered the costs of running the BBS, including the phone lines that users dialed into, but also curated the content and fostered a sense of community. This was a time when long-distance calls were expensive, so running a popular BBS could be a significant financial commitment.

Rheingold's observation about the "relatively low cost" of empowering individuals globally takes on new meaning when we consider the alternative publishing models of the time. Producing and distributing printed materials or broadcasting via traditional media required substantial resources. BBSs, in contrast, democratized access to information sharing, allowing anyone with a computer and modem to participate in discussions, share files, and even publish their own writing. This was particularly empowering for marginalized groups and those with niche interests who often struggled to find a voice in mainstream media.

His analogy to grassroots movements underscores the decentralized and resilient nature of BBSs. Unlike centralized information sources that could be easily controlled or censored, BBSs were scattered across countless individual computers. This made them difficult to suppress and allowed for a greater diversity of voices and perspectives. In essence, BBSs were an early embodiment of the internet's potential to foster free expression and connect people across geographical boundaries. They laid the groundwork for the online communities and digital publishing that we take for granted today.

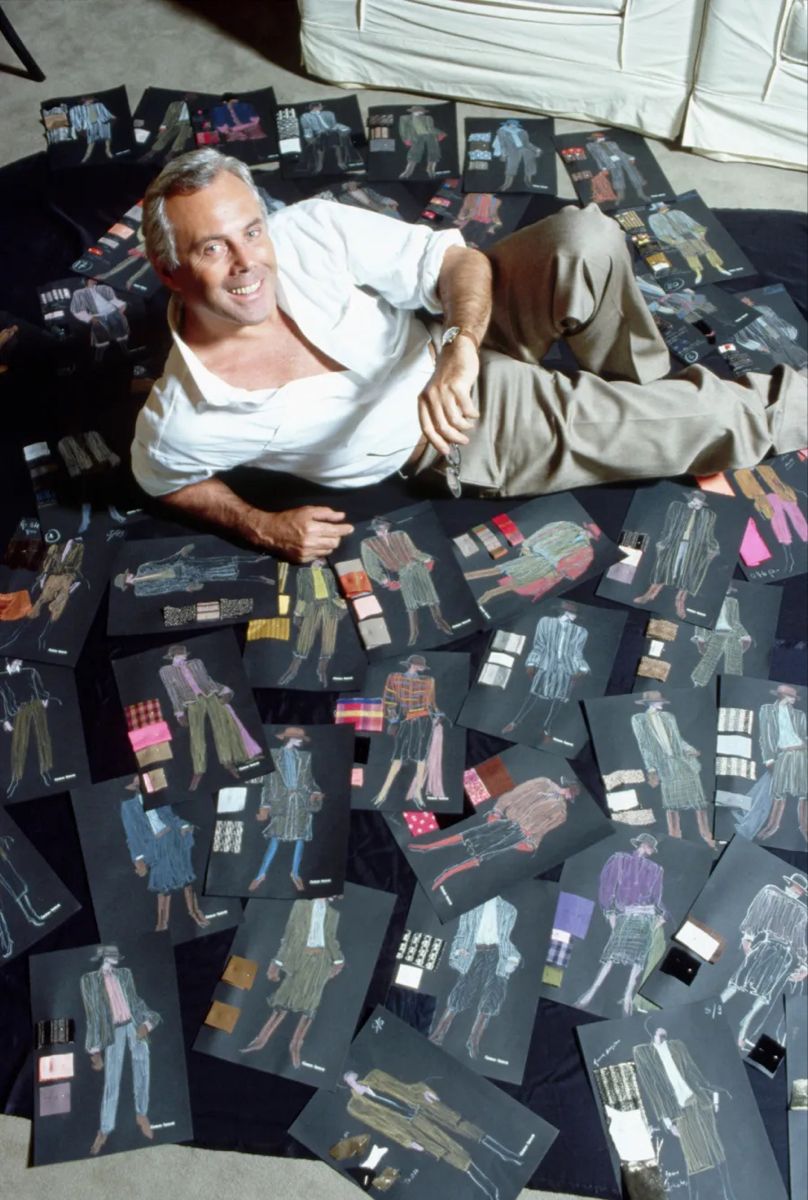

In the nascent days of personal computing, the mid-1970s saw the rise of Bulletin Board Systems (BBSs), online platforms that allowed users to connect and share information. These early online communities, accessed via dial-up modems and telephone lines, were a precursor to the internet as we know it today. However, accessing these BBSs was a technical challenge for many, hindered by the cost and complexity of modems. This is where Dennis Hayes stepped in. In 1977, amidst the backdrop of the burgeoning personal computer revolution and a growing DIY electronics culture, Hayes began producing affordable modems from his Atlanta home. This was a time when the world was just beginning to grasp the potential of computers, with companies like Apple and Microsoft emerging. Hayes, recognizing the need for a simpler and more accessible way to connect to BBSs, essentially democratized access to online communication. He hand-built these modems, meticulously crafting them on his kitchen table and even writing the accompanying manuals. This grassroots approach resonated with the burgeoning community of computer enthusiasts. His work led to the development of the "Hayes command set," a standardized language for modem communication that became widely adopted across the industry. Even today, the echoes of Hayes's work can be seen in modern modem technology, a testament to his contribution to the digital age. His efforts were pivotal in popularizing BBSs, transforming them from niche hobbyist platforms to widespread online communities that fostered the exchange of information, ideas, and even software. This laid the foundation for the online interactions and communities that are so central to our lives today.

To truly appreciate the impact of Dennis Hayes and his "Hayes commands," we need to step back in time to the early days of personal computing. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, computers were just beginning to enter homes, and the internet as we know it didn't exist. Communication between these isolated machines was a significant challenge.

Dennis Hayes, a young engineer, recognized this hurdle and began tinkering with modems, devices that could translate computer data into audible signals for transmission over telephone lines. He wasn't the first to invent the modem, but his innovation was to create a standardized command set – the "Hayes commands" – that allowed different modems to communicate with each other reliably. This was a crucial step in making modems more accessible and user-friendly. Imagine a world where every phone required a different way of dialing – that's what it was like before Hayes.

Hayes's impact extended beyond the technology itself. He hand-built modems in his kitchen and wrote the manuals that guided users. In a stroke of foresight, he included a section on potential applications, suggesting the idea of an electronic bulletin board. This sparked the imagination of Ward Christensen and Randy Suess, who in 1978 created the first public dial-up bulletin board system (BBS) called CBBS, in Chicago.

This was a revolutionary concept. Suddenly, people could connect with others, share information, and have discussions without needing to be in the same physical location. BBSs became incredibly popular, forming the foundation of online communities years before the World Wide Web. They were precursors to forums, social media, and even online dating. Think of them as localized, text-based versions of today's internet, where users dialed into a single computer, one at a time, to access the content.

The rise of BBSs was a cultural phenomenon. They provided a sense of community and connection in a pre-internet world. People could find others with shared interests, engage in debates, and access information that wasn't readily available elsewhere. Within 15 years, thousands of BBSs were flourishing worldwide, a testament to the power of Hayes's invention and his simple suggestion in a modem manual. This explosion of online communication laid the groundwork for the interconnected digital world we inhabit today.

During the second ONE BBSCON conference in 1993, Ward Christensen recounted the origins of CBBS (Computerized Bulletin Board System). To truly appreciate this pivotal moment, we need to step back in time to 1978. The world was a very different place then: no internet as we know it, no smartphones, and personal computers were a nascent technology, mainly the domain of hobbyists and enthusiasts. In January of that year, Chicago was hit by a blizzard of epic proportions, effectively shutting down the city. Confined to their homes, Christensen, a skilled programmer, and his friend Randy Suess, an electronics whiz, found themselves with time on their hands. They were both members of CACHE, the Chicago Area Computer Hobbyists' Exchange, a group eager to share information and knowledge about this exciting new technology.

Inspired by the community bulletin boards often found in public spaces, Christensen had an idea: what if they could create a virtual version using their computers? He set to work writing the software in assembly language, a complex and low-level programming language, on an 8080 CPU, one of the earliest microprocessors. Meanwhile, Suess, adept at hardware, built the necessary modem and connections to allow people to dial into the system. Their creation, CBBS, became the world's first public dial-up bulletin board system. This was a groundbreaking innovation. Imagine a world without email, instant messaging, or social media. CBBS provided a way for people to connect, share information, and have discussions, laying the foundation for the online communities we take for granted today. It was a crucial step in the evolution of computer-mediated communication, paving the way for the internet revolution that would follow.

The CBBS, an acronym for Computerized Bulletin Board System, emerged during a time of significant technological advancement and burgeoning computer culture. In the late 1970s, personal computers like the X-100, with its then-impressive 64K RAM, were beginning to enter homes and small businesses. These early machines, while groundbreaking, were limited by today's standards. Hard disks, which offered vast storage capacity, were prohibitively expensive, forcing users to rely on floppy disks with a mere fraction of the storage. Even the internet was in its infancy, with slow dial-up connections facilitated by modems like the Hayes MicroModem 100, crawling along at 300 bits per second. File transfers were agonizingly slow, making the exchange of information, even something as simple as a program or document, a tedious process often reliant on physical media like cassette tapes.

It was within this context that Ward Christensen, driven by the need for a faster way to share files with his friend Randy Suess, developed XMODEM, a simple file transfer protocol. This innovation, born out of necessity, laid the foundation for the CBBS. During a particularly harsh Chicago snowstorm in 1978, with the city blanketed in snow and movement restricted, Christensen had a flash of inspiration. He envisioned a system where users could connect remotely, share information, and engage in discussions. This idea, sparked during a moment of isolation, would become a cornerstone of online communication, paving the way for forums, online communities, and the social internet we know today.

To fully grasp the significance of this passage, it's important to understand the technological landscape of the late 1970s and early 1980s. This was a time when personal computers were just starting to emerge, the internet as we know it didn't exist, and the idea of connecting with others online was revolutionary.

Think of a world without the World Wide Web, without email, without social media. Communication was limited to phone calls, letters, and face-to-face interactions. Then imagine the advent of Bulletin Board Systems (BBSs), essentially online forums accessed through dial-up modems. These early BBSs, like the CBBS mentioned in the passage, were pioneering efforts in online communication, allowing users to connect with others, share information, and download files.

Dennis Hayes, a key figure in the development of modem technology, played a crucial role in popularizing BBSs. Modems were the gateway to these online communities, enabling computers to communicate over telephone lines. Hayes's efforts to catalog and share information about various BBSs helped to create a burgeoning network of users.

The mention of "Byte Magazine" highlights the importance of print media in disseminating technical knowledge during this era. Before online resources were readily available, magazines like Byte served as crucial sources of information for computer enthusiasts. The article by Christensen and Suess likely provided valuable insights into the workings of BBSs, further fueling their growth.

Finally, the establishment of "WLCRIS" and later "CHINET" foreshadowed the rise of free internet access. Randy Suess's initiative was a significant step towards making online communication accessible to a wider audience. This was a precursor to the internet revolution that would soon transform the world.

In essence, this passage offers a glimpse into the early days of online communication, a time of experimentation and innovation that laid the foundation for the connected world we live in today. It highlights the key role played by individuals like Dennis Hayes and Randy Suess, the importance of publications like Byte Magazine, and the gradual evolution towards widespread internet access.

In the early days of computing, before the internet as we know it existed, access was largely confined to the hallowed halls of universities and research institutions. Imagine a time when the World Wide Web was just a glimmer in Tim Berners-Lee's eye, and personal computers were a novelty! It was during this era, in the late 1970s, that a pioneering network called Chinet (the Chicago Network) emerged, offering a tantalizing taste of what was to come. Chinet provided free access to newsgroups and email for all its users, a revolutionary concept at a time when online communication was largely restricted to academic and government circles. This, along with the rise of Bulletin Board Systems (BBSs), marked a significant shift.

Think of BBSs as localized online communities, hosted on a single computer. Users dialed in with their modems – remember those screeching sounds? – to connect and engage in discussions, share files, and even play games. These early digital gathering places fostered a sense of belonging and camaraderie, much like the online forums and social media platforms of today. However, each BBS was like an isolated island in the vast digital sea. Communication between them was limited and cumbersome, relying on the goodwill of users who manually transferred messages or files from one system to another, much like passing notes in a classroom. This "sneakernet" approach, as it was humorously called, highlighted the need for a more interconnected system.

It wasn't until 1984, with the establishment of the first true BBS network, that these digital islands began to coalesce into a larger archipelago. This development laid the groundwork for the interconnected world we inhabit today, where information flows freely and communities transcend geographical boundaries.

In 1984, amidst the burgeoning era of personal computing and dial-up modems, Tom Jennings revolutionized online communication by establishing the first Fidonet network. He connected his own system, Fido BBS no. 2 in Baltimore, with another BBS, laying the groundwork for what would become the largest and most influential pre-internet online community. This was a time when the internet as we know it was still in its infancy, largely confined to universities and research institutions. BBSs, or Bulletin Board Systems, were localized, independent computer systems that users could dial into using their modems. They offered a digital space for discussions, file sharing, and games. Jennings' innovation was to link these isolated BBSs together, allowing users to exchange messages and files across vast distances. His creation, Fidonet, employed a store-and-forward system, where messages would "hop" from one BBS to another until they reached their destination, much like a digital relay race. This ingenious method circumvented the high cost of long-distance phone calls, making online communication more accessible. Moreover, the software required to operate a Fidonet node was freely distributed, fostering a grassroots, decentralized network that rapidly expanded across the globe. Fidonet's impact was profound. It not only connected people across continents but also nurtured a vibrant online culture. It was a precursor to the internet, pioneering many of the online communities and communication styles we see today. From online forums and file sharing to email and even online games, Fidonet laid the foundation for the modern digital world.

Fido BBS no. 1 was launched in San Francisco in December 1983 while its creator, Tom Jennings, was on vacation. This was a time when personal computers were just starting to become popular, and the internet as we know it didn't exist. People who wanted to connect with others online often used dial-up modems to access Bulletin Board Systems (BBSs), which were essentially online communities hosted on a single computer. The name "Fido" originated from a humorous incident at Jennings' former workplace. In the early 80s, companies often cobbled together their own computer systems from various parts, a far cry from the standardized hardware of today. Jennings' colleagues, during a casual after-work gathering, jokingly named one such makeshift machine "Fido" – likely a nod to its somewhat 'mongrel' nature and the loyal companionship a dog offers. A playful inscription of "Fido" on a visiting card, subsequently attached to the computer, became the namesake for the world's largest BBS network, Fidonet. Fidonet emerged in the mid-1980s, filling the void of a global network. It allowed different BBSs to exchange messages and files with each other automatically, usually late at night when long-distance phone rates were cheaper. This system, a precursor to the internet's email and file sharing, created a vibrant online community that spanned the globe, connecting people from all walks of life long before the World Wide Web became a household term.

In the early development of Fido, Jennings included a section for unmoderated messages, aptly named "anarchy," granting users complete freedom within this space. This reflected Jennings' unconventional personality and beliefs. He defied the stereotypical image of a programmer, sporting purple hair, advocating for anarchy and gay rights, and embracing a non-conformist appearance with metal adornments and a skateboard. This was the early 1980s, a time when the personal computer was just starting to enter homes, and the internet as we know it didn't exist. The dominant culture in tech was still very much straight-laced and corporate. Jennings, with his punk rock aesthetic and anti-establishment views, was a true outlier. His creation, Fido, was a reflection of his own desire for freedom and self-expression.

This anti-censorship ethos permeated Fidonet's management philosophy, which emphasized user autonomy and self-governance. The network was envisioned as a liberated platform where users collectively shaped the rules and norms. This was a radical departure from the top-down control that characterized other online systems of the time, such as CompuServe and The Source. Fidonet's decentralized structure, where each node operated independently, made it very difficult to enforce any kind of centralized censorship. This made it a haven for free speech and open discussion, attracting a diverse community of users with a wide range of interests and viewpoints. In a way, Fidonet was a precursor to the modern internet, with its emphasis on user-generated content and decentralized control.

To fully grasp the significance of Jennings' philosophy, it's crucial to understand the historical context in which it emerged. In the early days of online communication, the internet was a wild west of sorts, largely unregulated and populated by tech-savvy enthusiasts. Bulletin Board Systems (BBSs) like the one Jennings created were the primary hubs for online interaction, predating the World Wide Web and social media platforms we know today. These BBSs were often small, independent communities with their own distinct cultures and rules.

Jennings' approach to moderation was revolutionary for the time. It stood in stark contrast to the more centralized control exercised by CompuServe and other commercial online services. His emphasis on user autonomy and self-governance reflected the hacker ethos of the early internet, which championed freedom of information and individual expression. This approach was also a practical necessity. With limited resources and a rapidly growing user base, relying on the community to self-moderate was the most effective way to maintain order.

The Fidonet principles, "thou shalt not offend; thou shalt not be easily offended," encapsulate this philosophy. They highlight the importance of mutual respect and tolerance in fostering a healthy online community. This emphasis on self-restraint and understanding was crucial in a time when online communication lacked the visual and auditory cues of face-to-face interaction, making misunderstandings and offense more likely.

Jennings' vision of a self-governing online community has had a lasting impact on internet culture. While the scale and complexity of the modern internet have made his approach difficult to replicate fully, his ideas continue to inform debates about online governance, content moderation, and the balance between freedom of expression and responsible online behavior.

In the early days of online communication, before the internet as we know it existed, hobbyists were connecting their computers in a different way – through phone lines and a system called Fidonet. Imagine a time when the IBM PC was a cutting-edge machine, running DOS 2.0. This was the technology that powered the first Fidonet nodes. These weren't the sleek laptops and powerful desktops of today; these were the bulky, beige boxes that marked the dawn of the personal computer era. Fidonet was a grassroots movement, a decentralized network built from the ground up by enthusiasts who wrote their own software and shared it freely. This spirit of collaboration and open sharing was a defining characteristic of early online communities.

But connecting via phone lines came with a cost – literally. Every minute spent online meant money spent on phone calls. This financial constraint played a crucial role in shaping Fidonet technology. Programmers, many of whom were hobbyists themselves, focused on creating highly efficient software that could transfer data and messages quickly, minimizing those costly phone bills. This need for efficiency led to innovations in data compression and transfer protocols, laying the groundwork for the efficient online communication we enjoy today. Fidonet, born in an era of limited resources and dial-up connections, fostered a culture of resourcefulness and community-driven development that continues to inspire online communities today.

In the early days of computer networking, connecting machines often meant relying on existing telephone lines. This posed a significant challenge, especially in areas with limited or unreliable phone service. Imagine trying to send a file when even making a voice call was difficult! This is where Packet Radio technology emerged as a game-changer. Developed in the 1970s, it allowed computers to communicate wirelessly using radio waves, bypassing the need for phone lines altogether. Think of it as a precursor to today's Wi-Fi, but using radio frequencies instead. This was a crucial step in democratizing access to computer networks, particularly in rural communities or developing countries where telephone infrastructure was sparse. It's a testament to how innovation can overcome physical barriers and bring technology to more people. Amateur radio operators were among the early adopters of packet radio, experimenting with different protocols and applications. In fact, the AX.25 protocol, still used in some amateur radio applications today, was adapted from the X.25 packet-switching protocol. This grassroots development helped refine the technology and pave the way for its wider adoption.

Before the widespread adoption of the Internet, Fidonet played a crucial role in connecting people, particularly in developing countries. Imagine a time before the World Wide Web, when accessing information online meant dialing into a local Bulletin Board System (BBS) using a modem. These BBSs were often run by individuals passionate about technology, offering a platform for users to connect, share files, and engage in discussions. Fidonet, founded in 1984 by Tom Jennings, emerged as a network to link these BBSs together, enabling users to exchange messages and files across vast distances. In many regions of Africa, for instance, where traditional telecommunications infrastructure was limited, Fidonet's packet radio node served as the sole gateway to electronic communication, providing a vital link to the outside world.

During this era, the term "network" was virtually synonymous with "BBS," and Fidonet reigned supreme as the dominant BBS network, reaching users across the globe. It fostered a vibrant online community, facilitating the exchange of ideas and information among people who might otherwise have remained isolated. In 1988, a pivotal moment occurred when a gateway was established, linking Fidonet to the burgeoning Internet. This allowed Fidonet users to send emails to Internet users and access messaging services on both networks, bridging the gap between these two distinct online worlds.

Fidonet's popularity surged, leading to a rapid expansion. By 1991, it boasted over ten thousand nodes and tens of thousands of users, highlighting its significant reach. Just two years later, there were an estimated 60,000 BBSs in the United States alone, a number that dwarfed the number of web servers worldwide at the time. This underscores the crucial role Fidonet played in the early days of online communication, connecting individuals and communities before the Internet became a household name.

However, the technological landscape was rapidly evolving. With the advent of graphical browsers like Mosaic in 1993, the Internet's user-friendly interface and vast resources began to attract a wider audience. The growth rate of Internet nodes started to outpace that of Fidonet technology networks, marking a turning point in the history of online communication. While Fidonet's influence gradually waned, its legacy as a pioneering network that connected people and paved the way for the Internet's widespread adoption remains undeniable.

Introduction

Before the rise of the internet, Bulletin Board Systems (BBS) connected early digital pioneers through text-based forums, file sharing, and direct messaging. These forgotten networks fostered tight-knit communities, where users dialed in from home modems, sharing everything from tech tips to local news. BBS laid the groundwork for the online communities we know today, sparking a new era of digital social interaction.