Cutting off blood flow to the arms might sound counterintuitive, particularly when a heart attack is involved, as reduced blood flow typically leads to cell death. Yet in 2010, cardiologists discovered that this counterintuitive approach could help protect the heart from damage. This surprising result caught the attention of Dick Thijssen, a sport and exercise scientist at Liverpool John Moores University in the UK.

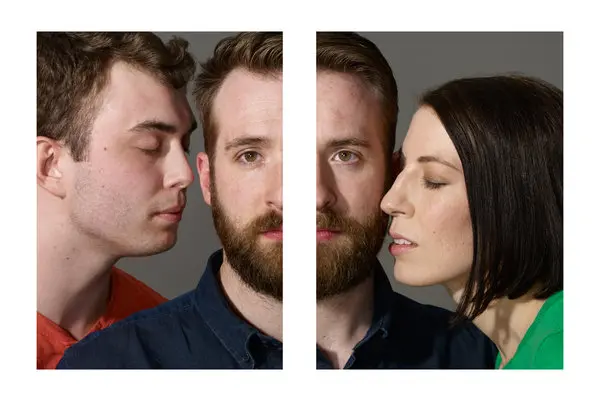

In the study, individuals who had experienced a suspected heart attack within the past 12 hours were treated with a pressure cuff placed over one of their upper arms. Under the guidance of Hans Botker and his team at Aarhus University Hospital in Denmark, the cuff was inflated and deflated in cycles of five minutes, repeated four times. The results were striking—there was significantly less heart tissue damage in those who underwent the procedure compared to those who did not.

Intrigued by the profound impact on heart damage, Thijssen wondered if the same technique, known as ischaemic preconditioning (IPC), could benefit athletes. To explore this, Thijssen and his colleagues conducted experiments on 15 healthy individuals who regularly engaged in moderate exercise. The volunteers were asked to cycle 5 kilometers as quickly as possible. With IPC as part of their preparation, participants shaved an average of 30 seconds off their times compared to their performance with a conventional warm-up.

The benefits extended to elite athletes as well. In one test, the England rugby sevens team demonstrated a 1% improvement in speed and reduced fatigue after incorporating IPC. Meanwhile, a study led by Emilie Jean-St-Michel at the University of Toronto showed that elite swimmers improved their 100-meter times by 0.7 seconds following IPC. This difference is significant; at the 2008 Beijing Olympics, the gap between bronze, silver, and gold in the women’s 100-meter freestyle was less than 0.3 seconds.

The mechanism behind IPC remains unclear. Some researchers speculate that the technique prompts the release of protective factors, but the exact substances and processes involved are still unknown. Moreover, the mechanisms safeguarding heart cells after a heart attack might differ from those enhancing athletic performance, adds Thijssen.

Despite the scientific uncertainty, many athletes are already experimenting with IPC in search of even the smallest competitive edge. Phil Glasgow from the Sports Institute of Northern Ireland, who works with Olympic athletes, notes that the method has gained traction across various sports. “Athletes are constantly seeking incremental improvements,” says Glasgow. "Even a 0.1% advantage can make a big difference."

0 Comments